We're off to Phoenix to visit family and celebrate my father-in-law’s 76th birthday. I don’t love Phoenix. Its sizzling, sprawling monotony grates on me after a few days. But Phoenix is where my husband’s dad and siblings live, so we go when we can. Family trumps all.

We're off to Phoenix to visit family and celebrate my father-in-law’s 76th birthday. I don’t love Phoenix. Its sizzling, sprawling monotony grates on me after a few days. But Phoenix is where my husband’s dad and siblings live, so we go when we can. Family trumps all.

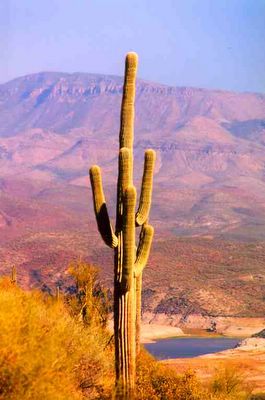

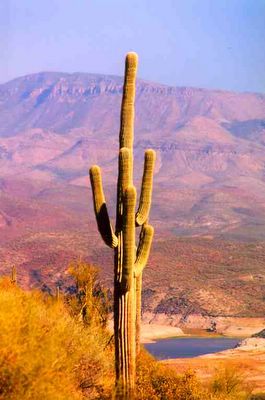

When our Arizona visits last more than a long weekend, I look for escapes and road trips that take us out of the flat, congested desert metropolis and into older, wilder places. Like the ancient cliff dwellings at Tonto and Montezuma Castle National Monuments. Or Jerome, a mountaintop gold-turned-ghost town that’s now home to artists and artisans and the boutiques, galleries and restaurants that blossom in their wake. Or the Apache Trail, one of the country’s great scenic drives (a fair stretch of it near Roosevelt Lake [above] on narrow, thrilling, cliff-hugging dirt). The road runs between Globe and Apache Junction, where, less than an hour from downtown Phoenix, you can hike in the Superstition Mountains or hunt for gold and ghosts in the Lost Dutchman Mine.

Phoenix and the Valley of the Sun it sits in hold treasures, too. A hike along trails in White Tank Regional Park brings you face to face with desert hills and their intriguing flora and fauna. Elegant, red rock Camelback Mountain and jagged, scrub-peppered Squaw Peak (recently renamed Piestawa Peak) rise from the valley floor, powerful visual antidotes to the city’s low, dry tedium. If you’re looking to meet fit, active Phoenicians, plan a hike or run up Squaw. Between Phoenix and its Sky Harbor airport sits Tempe, home of Arizona State University. Tempe’s a vibrant, funky place where rare, leafy trees line the oldest neighborhoods and the city center pulses like all good college towns.

But family’s why we go. Perhaps you have your own Phoenix. A place that won’t win any touristic beauty contests and isn’t at the top of your getaway hit parade, yet you visit and revisit to connect with family. And with memories. I wrote a story for Reunions Magazine that shares some of ours:

The Belanger Openby Lori Hein

As my husband’s mom’s multiple sclerosis worsened, my father-in-law moved her and his younger children from Massachusetts to Arizona’s gentler climate. Once grandchildren started to arrive, my mother-in-law, Bertie, longed to spend time with them all, both the Phoenix and Boston contingents. My father-in-law hatched the idea of an annual event that would have the Boston relatives spend three days each winter enjoying the Southwest sun and grandma’s company. To make the event irresistible, he built the reunion around golf. This was a masterstroke, as the family is full of avid golfers who love a little competition on the links. Bobby, my father-in-law, raised the interest level by constructing a whole tournament, complete with trophies and peppered with friendly wagers. The first Belanger Open was a hole-in-one and the next nine were just as perfect.

Planning for each golf reunion began about nine months before the tournament, with a Phoenix-area golf course located, inspected and nailed down as early as possible. Total costs were calculated and each family chipped in their share. Foursomes were established. Each tournament’s winner was responsible for booking the next year’s venue, with Phoenix relatives helping out, should the winner not hail from the Valley of the Sun. In the early years of the Open, only the golfers went to the course. The post-tournament party was held in grandma and grandpa’s backyard, with kiddie pools set up on the patio, and lines of little ones waiting for burgers and dogs. In later years, as finances allowed, we booked courses with private, kid-friendly function areas and had catered buffets. Litchfield Park’s Wigwam Resort, Superstition Springs in Mesa and Goodyear’s Palm Valley Golf Club all have function facilities. We’d gather there for about five hours, from the first foursome’s return to the early evening.

The Belanger Open grew over the years to include relatives from Florida and Pennsylvania. Golf was the big draw, of course, with one year seeing five foursomes tee off.

But the true main event was spending time with my mother-in-law: mom to some, Bertie to others, grandma to an ever-growing group of future golfers. Bertie was queen of the Belanger Open, delighting in the activities and the company of her grandchildren. The kids discovered grandpa’s golf cart wasn’t the only treat on wheels. Grandma’s wheelchair moved pretty fast, and her lap made a great passenger seat.

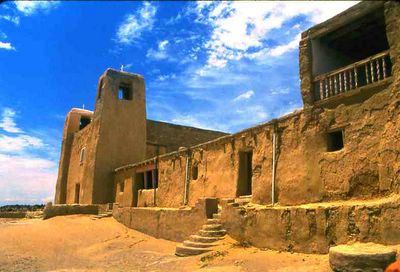

Each three-day reunion opened with a barbecue and horseshoe tournament at Uncle Tom’s or Uncle Rick’s. Cousins rediscovered each other, and we all caught up on family news. One year, a rented karaoke machine provided hours of great fun. We did some family-friendly local sightseeing on day two, taking Bertie in her wheelchair whenever possible. The Phoenix Zoo was a popular outing. Dinner at a restaurant on the second night gave us a chance to dress up. Fun, colorful Mexican restaurants worked great with kids.

Early on the third day, the golfers met at the course and took to the links. The non-golfers spent a leisurely brunch with Bertie. We gathered in the clubhouse function room in the early afternoon to toast the winner and roast the rest. Bobby would pass out Belanger Open t-shirts to all the kids and the final party would begin. My father-in-law loved passing out the trophies: Best Score, Most Improved Score, and Horse’s Behind for the golfer voted most deserving of that title.

After dinner we danced to music from an uncle’s portable boombox and the kids played with toys and trading cards from the stocked backpacks they’d brought. A professional photographer came by and took a group portrait that would be enlarged and mailed to each family. Bertie always sat proudly in the center of the front row.

After my mother-in-law succumbed to cancer, we put the Belanger Open on hold. We’ve begun getting together again, with some changes, but there’s always golf. And we’re sure Bertie is with us each time we gather.