When we arrived at the airport gate to meet our fellow travelers for our tour to Tibet, my husband Mike and I rested our eyes on the only group there, an animated knot of senior citizens. We, then in our 20s, exchanged eyebrow raises. Our journey would include a 700-mile overland drive from Lhasa, Tibet to Kathmandu, Nepal across some of the planet’s harshest high-altitude real estate, landscape so challenging that the tour brochures contained warnings to consult your physician before booking. We trusted that everyone had.

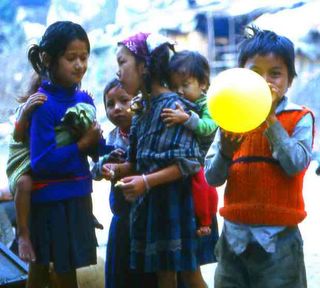

We bonded for a few days in Hong Kong before heading to the roof of the world. Except for us and 30-year-old sheep farmers John and Wimpy, our cohorts were septa- and octogenarians. We connected with raven-haired Lois, who wore dresses, hose and heels nearly every day, even in the Himalayas; Morris and Christine, sweet South Dakotans; elf-like Clarence from Calais, Maine, who wore a peaceful smile but rarely spoke; and Bob, who brought yellow balloons that he blew up whenever kids were around. We were 32 in all, well-traveled and open to adventure.

Our first Tibet days brought magic: the hilltop Potala, once the palace of Dalai Lamas; temples lit with yak butter lamps and filled with chanting monks and earnest pilgrims; prayer wheels turning and prayer bells tinkling; yak skin boats and fields of golden mustard; aquamarine lakes and Earth’s mightiest mountains.

But as we moved farther from Lhasa and up onto the otherworldly central plateau, where nomads roamed, settlements sat a day apart and roads ran at 15,000 feet, things changed.

None of us had expected creature comforts. We were prepared for the dust, wind, rough roads, washouts, intense sun and altitude sickness that are the minimum price of admission for visitors to this astounding land. But we were unprepared for other costs that accrued as Lhasa began to feel like a distant memory, Kathmandu like a far-off dream. We had a tough in-between.

Food and water went first. When we passed through towns we’d stop at local restaurants and eat sausage, barley dumplings and acrid yak butter tea. Otherwise, we ate from the back of our microbuses, which had purportedly been packed with enough staples to last until Nepal. We enjoyed the spartan picnics until the day we realized that rationing had begun. The guides no longer opened the tailgate and let us take what we wanted. Instead, they’d place broken bread and a few cans of Spam, stewed tomatoes and mandarin oranges in a box, lay it on the ground, and invite us to divvy up the contents. The canned tomatoes and oranges were prized because they contained juice. Our water was almost gone, and for days we’d been traveling across Tibet not only hungry, but dehydrated. And, if you were Morris and Christine, who’d quietly mentioned they were diabetic, scared as well.

Leadership went next. We had two guides: the tour company’s American guide, whom I’ll call Bert, and Lu, the Beijing-based guide assigned by the Chinese government, which rules Tibet. Each wanted to be top dog. Instead of cooperating, they stopped communicating. We would pay dearly for that.

We’d been told before leaving home that a landslide had rendered impassable a stretch of road just beyond the Tibet-Nepal border crossing. Helicopters, we were told, would meet us and airlift us over the slide.

We arrived in the Tibetan border town that sits on a mountainside above the bridge linking Tibet and Nepal. Everyone hikes down, as there’s no road. We settled into a hotel at the lip of the border trail and slept.

In the morning we joined a parade of border-crossers. Queued up to exit China were traders with boxes strapped to their backs; laborers; local families; chiseled French couples in technical fabrics; sturdy Germans with walking sticks; backpacking Americans; a young solo woman with a beaming face and hair tucked under a white bandana; us, and the porters Bert had hired to carry Lois, Clarence and our baggage. Clarence, whom I feared would be catapulted from his porter’s back and into the ravine below, smiled the whole way down.

Mike and I reached the border in under an hour. It would be four hours before the last of our seniors, Morris and Christine, stumbled into Nepal. They were spent, unsteady and starving.

We turned to Bert, expecting to be led to helicopters. There were none. Bert was to have called the air station from Tibet to give our expected arrival time, a call that required dialing through Chinese channels. But because he and Lu weren’t speaking, he’d never asked for the help needed to make that call. Lu, who’d said goodbye up in Tibet, was on his way home to Beijing. We were in Tatopani, Nepal with Bert and no helicopters. It started to rain, and some of us started to cry.

After securing lodging in the grain lofts of a dozen Tatopani homes, Bert announced that in the

morning we’d walk over the slide. Five miles. We scrounged food at a Tatopani shop, watched Bob blow balloons for Tatopani’s kids, then turned in, using our clothes as blankets. Mike and I shared a loft with Morris and Christine, who said a prayer in the dark.

Landslide day dawned hot, and before we’d tucked away the first rough, uphill mile, we knew that for this group, average age 68, coming out the other end whole was not a given. Clarence, Lois and a few others had arranged to have themselves carried over the slide on porters’ backs. I don’t know what they paid, but had it been the moon, it was a bargain.

Morris and Christine walked. Mike, John, Wimpy and I stayed with them. Hours passed, and things turned bad. Unforgiving sun, relentless up-and-down, no food or water. Morris and Christine began sitting a lot, and we did what little we could to keep them moving forward. After about two hours, Christine’s body quit. She fainted on the trail. Morris sat on a rock and wept.

“Hello. I’m Bea. I’m a nurse. Can I help?” From nowhere appeared the woman I’d seen the day before, the solo traveler in the white bandana. We told Bea about the diabetes, lack of food and tremendous recent stress. Bea comforted Morris, then set to reviving Christine and checking her vitals. Bea, a New Zealander who was in the Himalayas “just wandering,” produced a bag of granola and a canteen of water. She fed Christine and swabbed her head, and Christine’s color returned.

Bea said she’d “heard” it was still a four-hour hike from where we sat to the landslide’s end. “She can’t walk that,” said Bea. As if on cue, three Nepalese men in shorts and cloth shoes appeared. Bea, whose talents included fluency in Nepali, discerned that they were porters, and she hired them to carry Christine. While one carried Christine on his back, the others supported Morris, then they’d switch off.

When we finally came off the slide at the village of Bhirabaise, our group and half the villagers rushed to greet us. When we turned to thank Bea, she was gone.

www.LoriHein.com

Wood carvings might be the world's most ubiquitous souvenir. You can find "traditional local crafts" made of wood nearly anywhere with trees and tourists.

Wood carvings might be the world's most ubiquitous souvenir. You can find "traditional local crafts" made of wood nearly anywhere with trees and tourists.