We'd been traveling across the Tibetan plateau for some two weeks. Tibet, the raw, rugged roof of the world, is one of Earth’s remotest and most exotic destinations, but travel there is physically punishing. Tibet fills you up and saps you utterly, all in the same moment. Our journey was nearing its end, and we all looked forward to crossing the border into Nepal. In Kathmandu there’d be hot food and hot water, and we dreamed of these. We had savored our trek across Tibet, but we were spent.

We’d had our share of broken roads and landslides. We’d helped Pinzo, our strapping driver with his thick shock of black hair and patient twinkle in his eyes, push our little bus out of countless mud holes and swollen streams. We’d dodged rabid dogs. We’d been eating cold stewed tomatoes straight from the can for days, sucking down the juice to relieve our dehydration and to take in every possible gram of vitamin C we could get our lips on. We couldn’t remember our last shower or change of clothes.

At Zhangmu, Tibet, we made our way down a mountainside to the Friendship Bridge that links China to Nepal at Kodari. The hike was too steep and grueling for a few older members of our group, so they hired nimble-footed porters to carry them across the border on their backs. Our itinerary called for a bus to meet us in Kodari and take us to a site where helicopters would ferry us over a wide, severe landslide area. Once over the slide, another bus would meet us and take us to Kathmandu. That was the plan.

But plans go awry. We had inept tour guides who squabbled amongst themselves and failed to consider that helicopters don’t just appear from thin air to pick up tourists. Somebody has to call them first. And nobody had. We’d end up walking over the slide the next day, a challenge that would take 10 hours.

But first, we had to find somewhere to spend the night. We were driven to Tatopani, Nepal and left in the middle of the town’s dirt main street. Trekkers on Nepal’s Annapurna circuit use Tatopani as a rest stop, and when we arrived there weren’t enough rooms in the town’s few basic lodges to house us. We were filthy, frustrated, hungry and exhausted, and there was no room for us at the inn.

Then something remarkable happened. The people of Tatopani opened their hearts and homes to us. A handful of farmers and herders and merchants found space for us in the lofts of their wooden houses. They rolled crude mats onto the straw-covered plank floors and told us we were welcome.

After we’d all laid claim to a mat somewhere, we gathered in the street. We hadn’t eaten since morning, so we made plans to buy and share whatever meager edibles were available on the dusty shelves of Tatopani’s few tiny stores.

But before we could start shopping, a man called to us from a narrow wooden house. He opened the door and windows as wide as they would go and invited us all inside. A woman stood over a kettle that hung on a tripod over a wood fire. Steam billowed from the pot, and something smelled fresh, hot and wonderful. The man had set up a few tables in his front room, and we all sat down. After a few minutes, the woman set a huge platter of boiled yellow potatoes on each table. And a bowl of salt. We had no plates or cutlery. Just fingers, beautiful, round, creamy, butter-colored potatoes, and salt. We picked up the hot, skinned potatoes, dipped them into the salt, and ate the best meal of our lives. I will never forget how those Tatopani potatoes tasted, coated with healthy chunks of salt, as they slid around my mouth in that dark, smoke-filled room turned into a makeshift restaurant just for us.

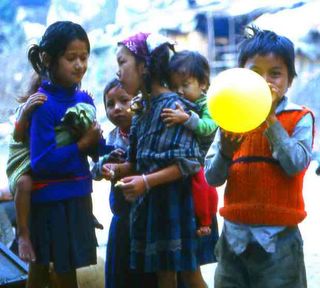

Sated to our bones, we thanked the family and moved outside. By now, everyone in the village knew of us and our unplanned overnight stay, and they smiled and nodded as they passed us in the street. A group of children, some with tiny brothers or sisters in bundles on their backs, stood studying us. One of our fellow travelers reached into his pack and pulled out a bag of yellow balloons. He began blowing them up, and the children moved closer. Within a few minutes, nearly every kid in Tatopani held a yellow balloon.

Some of the balloons got away and bounced down the dusty road. I watched them roll away, like giant, magical, yellow potatoes, and thought how lucky we were to be stranded in Tatopani.

Where shall we go next?