November 17, 2011

Dreams and weavers

The Ojibwa made the first dreamcatchers, fashioned to resemble spider webs, from willow hoops and dyed yarn or plant fiber, and hung them above their babies' cradles. Like a spider web, made to catch and hold, the manmade webs caught harm or evil that might float above an infant's bed and also captured the child's good dreams, letting bad ones slip through the net and into the night.

www.LoriHein.com

June 21, 2010

Luna moth: hello, good-bye

Last weekend was our family's 24th annual Birthday Bash, a reunion built to collectively celebrate the many summer birthdays among members of our clan. Mike and I host the bash at our New Hampshire cottage, and lobsters-for-all is our birthday gift.

Last weekend was our family's 24th annual Birthday Bash, a reunion built to collectively celebrate the many summer birthdays among members of our clan. Mike and I host the bash at our New Hampshire cottage, and lobsters-for-all is our birthday gift.

Our cottage is on a seven-mile-long, spring-fed lake in New Hampshire's Monadnock region, in the state's southwest corner. It's a beautiful part of the state, with outdoor opportunities galore and postcard-perfect New England towns. And, when you've had your fill of gorgeous green spaces and quiet clapboard beauty, you've got Keene, a small, funky, live-and-let-live city with cool shops and restaurants and America's widest Main Street. (Jumanji was filmed here, and Main Street is the venue for the animal stampede...)

Some special guests crashed this year's bash: three electric green, saucer-sized luna moths. In the 27 years we've owned this property, I've seen luna moths there only once before. (Adam's been going to the cottage with his fraternity brothers and says he sees lunas "all the time," but I'm thinking that's the Bud Light talking.)

The moths, whose lifespan is a single week, were our guests of honor. They settled themselves for their last days on Earth at our house's busiest place, on the siding next to and the stoop just in front of the front door.

We were 17 partying people of all ages, from three states, eager to catch up with each other and enjoy a weekend in the sun. But we were mindful of our special guests. That they picked our place to live out their short lives filled us with awe.

"Careful, everyone! A luna moth has now moved onto the porch flooring, by the doormat! Be careful! Luna moth is RIGHT NEAR THE DOOR when you come in or out!" As the moths shifted position during their stay on our stoop and siding we made sure everyone knew to look out for them.

Then they died. Two disappeared to die unseen, but the biggest one expired as we watched, moving from his vertical hold on the siding to a flat step. My brother-in-law, Chris, took on the job of moth monitoring, and he knew exactly when the exquisite creature passed away.

"He's dead," said Chris.

Chris put our luna moth on one of the white Chinet plates I'd used to serve the bash food. Chris walked around the yard and made sure everyone saw the luna on the plate; he'd been a friend, and this was his wake.

Mike got an old pickle jar he'd used to hold nails from the garage and carefully put the luna inside.

www.lorihein.com

September 09, 2008

Clarence DeMar Marathon: A run through quintessential New England

Last Friday I ran a 20-miler, the longest and last of the really hairy training runs I needed to tuck away in order to prepare for the Clarence DeMar Marathon, which, God willing, I'll start and finish on September 28.

Last Friday I ran a 20-miler, the longest and last of the really hairy training runs I needed to tuck away in order to prepare for the Clarence DeMar Marathon, which, God willing, I'll start and finish on September 28.I ran the DeMar once before, in 2006, and it was a nightmare experience, so I have to run it again to replace the bad memories with better ones.

Two days before the race I got the flu: fever (which broke two hours before I had to leave for the start line), chills, vomiting, dehydration, sore throat. All the food and liquid I took in during those days served only to heal me and get my body back to its normal state and not to fuel me for the marathon. My intake was spent, not stored. Hence, I started the race depleted and suffered through nearly four and a half hours of indescribable agony. Divine intervention got me to the finish. As my mother reminds me whenever the subject comes up, I was foolish for having started at all. I will never do that again.

I'm looking forward to this year's race, named after Olympian and seven-time Boston Marathon winner Clarence DeMar, because it's a lovely run through some of the best scenery New England has to offer, scenery I missed in 2006 because I could barely lift my head from my chest.

The race starts in Gilsum, New Hampshire, a hilly burg of some thousand souls and home of the Rock Swap, an annual June gathering of collectors and geology buffs. The DeMar is a small marathon that attracts a few hundred runners, and the starting line is in front of the Gilsum General Store. Before the gun goes off, the runners rest and stretch on the lawn or front stoop of the Gilsum Congregational Church (which hosts the Rock Swap's Ham and Bean Supper). That's flu-riddled me in the photo sitting on the stoop wrapped in fleece-lined sweats, three layers of shirts and coats, and a hat. About a half hour before the start, the low-key character of the race is personified by the guy in overalls who walks down Main Street calling, "If ya want yer bags to git to the finish line, throw 'em in the back of that pickup over there. It's leavin' now."

The race's early miles are its loveliest and parallel the rushing, curving Ashuelot River. In Surry, we run through an area of fields, farms, flowers and stunning Colonial clapboard-clad architecture.

The race ends in Keene, one of my favorite small cities. After crossing the finish line on the campus of Keene State College in the heart of downtown, runners are treated to steaming vegetable soup, massages and free hot showers in the basement of Spaulding Gym.

This time around, I hope I'll be healthy enough to enjoy my run through quintessential New England.

www.LoriHein.com

July 03, 2008

Uncrowded America: Bikers, fish and one old grouch

We're about to take off for the Fourth of July weekend. We're spending it, as we always do, at our place in New Hampshire's Monadnock region. While I can't wait to get there and crack a beer, I'm not looking forward to being on the highway for the next four hours with thousands of other people. Four-dollar a gallon gas notwithstanding, the roads will be mighty crowded this afternoon.

We're about to take off for the Fourth of July weekend. We're spending it, as we always do, at our place in New Hampshire's Monadnock region. While I can't wait to get there and crack a beer, I'm not looking forward to being on the highway for the next four hours with thousands of other people. Four-dollar a gallon gas notwithstanding, the roads will be mighty crowded this afternoon.Makes me nostalgic for some of the uncrowded places I've seen in my journeys around America.

Like Sand Cut, Florida, the "Speck Capital of the World." This little burg sits on Lake Okeechobee, the best spot in Florida to fish for speck, also known as speckled perch or black crappie. Sand Cut gets a lot of fishing visitors but has a permanent population of fewer than 10 souls, including the "old grouch" who merits mention on the hamlet's welcome sign.

January 07, 2008

Common sense takes a vacation

I went to our New Hampshire place last week. It's beautiful in any season, but when it's snowbound it looks like a fairy cottage. Glorious, white, sun-glinty. Icicle swords rooted to trees and eaves and railings, catching sun and bouncing light all over. Animal tracks large and small captured in frozen crisscrosses on the buried lawn.

I'd gone to the cottage to clean up after my son and his friends, who'd spent a week of their college semester break there. Except for the furry Chinese food stuck to some plates in the sink, things looked pretty good. The kids had spent some of their time outside -- they left a Stonehenge-shaped formation of beach chairs, now cemented in place by hardened snow until spring, on the deck -- but I saw no evidence of reckless vacation behavior.

Nobody had, for example, jumped off the roof into the eight-foot-high snowdrift that billows up against the house each winter. Adam had evidently absorbed at least one of our 237 recountings of the day, years ago, when our friend Larry leapt from the roof into the drift, expecting to be pillowed by softness but drilling instead through the snow and crashing full-force onto the boulder the drift covered, shattering his ankle and compromising it for life.

I did, however, see reckless vacation behavior as I drove home. It was school vacation week, and kids were out everywhere enjoying the snow. As I drove above a railbed that paralleled a half-frozen river, I watched two young boys ride snowmobiles down the railroad tracks. Their dad, who'd parked his turquoise pickup on the railbed about three feet from the tracks, accompanied them on his own machine. Dad took up the rear, and the smallest, youngest boy led the pack. The tracks weren't arrow straight -- they wound and curved, mimicking the bends in the river -- so the snowmobilers wouldn't be able to see trouble barreling down the tracks.

This oblivious trio called to mind people I've encountered in far-flung places who seem to think tempting fate is part of the travel experience.

Letting your common sense take a vacation just because you're on one isn't just foolish, it can be deadly. You don't take your kids snowmobiling down active railroad tracks; you don't sit your toddler atop a buffalo in Yellowstone for a photo op; you don't squeeze yourself aboard a tiny, overloaded wooden ferry that has no life jackets.

And, unless you're trained for it, you don't walk across a glacier without a guide.

We were driving Alberta's superb Icefields Parkway from Lake Louise to Jasper and made a pit stop at the Columbia Icefields Visitor Centre, where we boarded a mammoth Sno Coach for a ride up the Athabasca Glacier, a tongue of ice 10 miles long.

As the coach climbed the Athabasca, we looked to our right across a half-mile expanse of crevasses and cracks and great snow chunks heaved up into wild formations and saw two figures walking up the glacier, unguided and without equipment of any kind.

Our guide shook his head. "They shouldn't be out there alone," he said. "They don't know where to walk, where the thin layers of crusty snow are that hide crevasses. They fall in and die." He then told us about the Athabasca's most recent victims, all tourists who'd figured hiking up this monstrous field of ancient, moving ice was just a walk in the snow.

The fools kept hiking higher and higher and farther and farther away from the guided tour areas and activities. Our guide kept one eye on them as he treated us to a safe and thrilling tour of the glacier.

As we boarded the coach for the trip back down to the visitors' center, I scanned the upper reaches of the icefield for one last fix on the two hikers. I didn't see them.

November 13, 2007

Bare trees and docks with knees

Leaf cleanup was the de rigueur activity in my neighborhood this weekend, with most menfolk out raking or blowing golden leaves into piles, then bagging and hauling them to secret sites whose owners may or may not have given dumping permission. Mike dumps our leaves behind the fire station, which, because of the station's decision to let people toss their rotted, post-Halloween pumpkins back there, has become a fecund pumpkin patch. So many pumpkins grew from the detritus of last year's jack-o'-lanterns that this fall the firefighters handed out free pumpkins to kids in town.

Leaf cleanup was the de rigueur activity in my neighborhood this weekend, with most menfolk out raking or blowing golden leaves into piles, then bagging and hauling them to secret sites whose owners may or may not have given dumping permission. Mike dumps our leaves behind the fire station, which, because of the station's decision to let people toss their rotted, post-Halloween pumpkins back there, has become a fecund pumpkin patch. So many pumpkins grew from the detritus of last year's jack-o'-lanterns that this fall the firefighters handed out free pumpkins to kids in town.I wrote a story a few years back about fall and fallen leaves and the slow turn of my part of the earth from warmth to chill. I usually manage to get "The Last Paddle" published somewhere in October or November --this story with shedding deciduous trees as supporting characters is one of my stock of evergreen articles, stories with long reprint lives that I'm able to resell year after year. I blew it this year, though, and didn't get the piece to editors early enough -- if you haven't sent your fall-themed story off for consideration by Mother's Day, you're too late.

Here on Ribbons of Highway, I'm the editor, so here's the story:

The Last Paddle

Lori Hein

Foliage is long past peak and many trees are already barren. The graying leaves that still hang on quake with age and inevitability. I push my kayak into the water and paddle over and around the stumps revealed each fall, when my lake is peeled back to show things unseen in summer.

Fishermen and weekenders have gone. Time to pull the stopper, inspect the dam and make needed repairs. By late autumn, the lake in its shallowest parts will be a ripe mud pool. In its deepest, a meandering, watery ribbon.

It’s the season’s last paddle. The low water can no longer host powerboats, and even the most committed bass men in their silvery, shallow-hulled craft have quit the lake until spring. When the lake is down, my kayak shows me things no one else is looking for in places no one else can reach.

I wear sunglasses. Burnished light glints off the ripples through which I ride. I tilt my face toward the sun, remembering how it felt in summer, and I try to soak it up and store it.

As I glide through this spare autumn waterworld, I discover a rock jetty, hand-placed a century ago, running long and low off an island’s tip. The line along the shore where earth’s fecund layer of forest soil ends and its granite underpinnings begin. Decaying logs and slender water grasses that house creatures, some who show themselves and some who scuttle away. I peer into their murky homes and breathe the deep, cloying smell of exposed algae. Hello, turtle. Let me sit and examine the pattern on your shell.

Like spotlights, the stillness and bare branches let me see or sense any moving thing. A few year-rounders putter about their cottages, canoes on shore, lawn furniture still arranged. Two fishermen are closing their place, pulling up docks and securing windows. Their dog explodes from the woods when he sees my blue boat, a burst of movement and color in this muted, going-to-sleep world, and he bounds along the shore next to me until dense trees stop him.

I eavesdrop on a couple in a birch bark canoe. They’re a quarter-mile away, but I hear their conversation—speculation about which yard a moose had called home for a while—as clearly as if I were sitting between them. Were I to confirm, in my normal voice, that they’d indeed found Lily Moose’s bed of now shrivelled flowers, they would hear me, crystal clear.

Dennis the dentist has been spending less time on teeth and more on the lake of late, and he poles around on a homemade raft, collecting slimy, untethered logs that poke from the mud near his dock. He’s a fit man with Ralph Lauren hair sharing raft space with dripping, brown butt ends of rotted trees.

When the water is down, the docks left standing in the muck become long-limbed flamingos, skinny legs and knees exposed. Can-can girls. Frisky ladies pulling up their skirts. The docks that have been hauled out and tied upright to trees show their shiny plastic barrel bellies.

Anything that can blow away has been stored away. Gone are wind chimes and floats, umbrellas and beach chairs. Lonely picnic tables, too heavy to move, dot beaches and yards. They’ve begun their slow, cold wait for weather that will again pull people back outside to sit.

At the marina, docks and boat berths are pulled out. The gas pump is gone. White shrink-wrapped motorboats sit on land like so many Sydney Opera Houses. In the extreme silence, my ears track the progress of a car as it travels from the lakeshore up to the top of a wooded mountain.

On this last paddle, I do things I don’t do when the water is high and others are about. I cross the lake at its widest point, slowly. Today, no need to rush. No worry about powerboats overtaking me before I reach the other shore. I cross and recross. I stop paddling and float with head back and eyes closed, stamping this serene time into my memory.

The loon that lives with his mate in a reedy shallow wants to play. He dives under my kayak and emerges, finally, twenty yards off its other side. The waterfall whose hums and trills are muted in season by the competing sounds of summer activity now has top billing. From my gently rocking seat, I take in its performance.

As I head home, the day’s last rays kissing the earth, I look down the lake and think of what’s ahead. Winter will soon bring its wonders. Like the long skate. If you catch it just right, after the lake freezes but before snow has buried it, you can skate on glass for seven miles.

www.LoriHein.com

October 09, 2007

Provence: Two traveler-tested villa rentals

My sister, Leslie, returned from an August trip to Provence with rave reviews on two properties she rented with her family. Renting abroad is one of my favorite ways to travel, so I thought I'd share Leslie's comments and links to the properties she rented. (See my June 14, 2007 post for tips on renting property abroad -- there is a key out there with your name on it.)

My sister, Leslie, returned from an August trip to Provence with rave reviews on two properties she rented with her family. Renting abroad is one of my favorite ways to travel, so I thought I'd share Leslie's comments and links to the properties she rented. (See my June 14, 2007 post for tips on renting property abroad -- there is a key out there with your name on it.)Said Leslie about her rental near St. Remy, France, where Vincent van Gogh painted Starry Night:

"Loved the hospitality of the host. And the place itself - you really need to see this place. It was huge - a big bastide or Provencal-style farmhouse. It had so much character, so much property, a great built-in pool and hammock and boules court. Just wonderful. Felt like we were living the Provencal life." Check it out at www.romanil.com:80/anglais.htm .

Of her rental in Nice, she said:

"Loved the location - across the street from the beach -- the Riviera -- on the Promende des Anglais and just down the street from the Negresco Hotel (photo) and great dining. Also, a fabulous kitchen and bathroom and an area outside where you could eat, relax, read. The water at the beach was gorgeous - bright blue and pristine." Check out this property at www.vrbo.com/9192 .

And, while you're checking out vacation rental listings, take a look at my sister's place in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Available year-round, it's a beautiful base from which to enjoy foliage season or to ski, swim, golf, bike, hike, relax... Find it here: www.cyberrentals.com/NH/SullNHWV.html .

www.LoriHein.com

July 18, 2007

The sounds of Harlech

"Go in and look at it," said Dana.

I know nothing about harps but do have some sense of the value of quality musical instruments. Getting out of the car, I said, "I bet it's about four grand..."

It was ten minutes to six, and the store closed at six, and I didn't want to get the shop owner excited about potentially selling a harp in the very last moments of his business day, so instead of going into the store I went to the window, hoping to see a price tag. Dangling off the harp was the cardboard tag: "549.00."

I couldn't believe it. I mouthed oh-my-god-type words to Dana, who was watching me from the car. I went back to the car and got in. "It's only five hundred and forty-nine dollars!" said I, who, again, knows squat about harps. I don't know if $549 is good or bad, but it sounded cheap to me for a gorgeous instrument shaped like a giant heart that could sit regally on my living room floor next to the piano.

I imagined my fingers running over the strings. I figured I could learn to coax music from it fairly quickly, as I inherited by grandmother's ability to "play by ear" (a skill, my mother tells me, that skips a generation -- neither of my kids can do it, so maybe one or more of my future grandchildren will be able to jam with me someday, with grandma perhaps on harp).

"Buy it!" said Dana. "Just buy it. You know you want it. If you don't buy it, you'll just keep thinking about it."

I considered rushing in and scooping up the harp with five minutes to go until closing time. The owner would be floored. Things like this just don't happen -- middle-aged women running in off the street with five minutes to closing saying, "I'll take that harp!" and handing over the plastic equivalent of five and a half C-notes.

"It would look good in the living room, wouldn't it?" I said. "Five hundred and fifty dollars. That's big for an impulse buy, but for a beautiful harp, it sounds almost free. Dad would laugh. 'Honey, I'm home. And I have a harp in the back of the car.' He'd just laugh."

I didn't buy the harp, but the fact that I'm writing this post about it a full day later proves I'm still thinking about it...

I've loved the look and sound of the harp since a day years ago when I stood on the great, gray stone walls of Harlech Castle in western Wales and watched a harpist who'd ensconced himself in the castle's inner courtyard. As we tourists walked walls and climbed towers, the harpist ran his fingers across some 40 strings and created magical music.

Sounds are part of a place, and my Harlech soundtrack has three parts:

The song, which I've been playing on the piano since I was 10, that put Harlech on my radar screen to begin with, the robust Men of Harlech, a mighty tune written to extol the courage of Welsh forces against the English during the 15th century War of the Roses; the rhythmic crash of the sea onto the shore beyond Harlech Castle's rocky promontory; the lone harpist in the castle courtyard.

Strong, elegant sounds.

We're going to New Hampshire next weekend. I hope the harp is still there.

www.LoriHein.com

October 16, 2006

A ride through low water in WaveLength Magazine

I take you on a low water autumn kayak ride through muck, reeds and shallows in the Fall 2006 issue of WaveLength Magazine. At its Web site, www.wavelengthmagazine.com, the paddling sports publication lets you download the current issue so, for a while at least, you can read the story there in all its PDF glory if you'd like. Some magazines and editors are a pleasure to work with, and I count WaveLength in that company. They're located in the relative wilds of beautiful British Columbia, and I got a bonus when I received their package with my copy of the fall issue and my paycheck: the envelope was festooned with colorful, interesting Canadian stamps to add to my stamp collection.

Enjoy the essay:

The Last Paddle

Lori Hein

Foliage is long past peak, and many trees are already barren. The graying leaves that still hang on quake with age and inevitability. I push my kayak into the water and paddle over and around the stumps revealed each fall, when my lake is peeled back to show things unseen in summer.

Fishermen and weekenders have gone. Time to pull the stopper, inspect the dam and make needed repairs. By late autumn, the lake in its shallowest parts will be a ripe mud pool. In its deepest, a meandering, watery ribbon.

It’s the season’s last paddle. The low water can no longer host powerboats, and even the most committed bass men in their silvery, shallow-hulled craft have quit the lake until spring. When the lake is down, my kayak shows me things no one else is looking for in places no one else can reach.

I wear sunglasses. Burnished light glints off the ripples through which I ride. I tilt my face toward the sun, remembering how it felt in summer, and I try to soak it up and store it.

As I glide through this spare autumn waterworld, I discover a rock jetty, hand-placed a century ago, running long and low off an island’s tip. The line along the shore where earth’s fecund layer of forest soil ends and its granite underpinnings begin. Decaying logs and slender water grasses that house creatures, some who show themselves and some who scuttle away. I peer into their murky homes and breathe the deep, cloying smell of exposed algae. Hello, turtle. Let me sit and examine the pattern on your shell.

Like spotlights, the stillness and bare branches let me see or sense any moving thing. A few year-rounders putter about their cottages, canoes on shore, lawn furniture still arranged. Two fishermen are closing their place, pulling up docks and securing windows. Their dog explodes from the woods when he sees my blue boat, a burst of movement and color in this muted, going-to-sleep world, and he bounds along the shore next to me until dense trees stop him.

I eavesdrop on a couple in a birch bark canoe. They’re a quarter-mile away, but I hear their conversation—speculation about which yard a moose had called home for a while—as clearly as if I were sitting between them. Were I to confirm, in my normal voice, that they’d indeed found Lily Moose’s bed of now shrivelled flowers, they would hear me, crystal clear.

Dennis the dentist has been spending less time on teeth and more on the lake of late, and he poles around on a homemade raft, collecting slimy, untethered logs that poke from the mud near his dock. He’s a fit man with Ralph Lauren hair sharing raft space with dripping, brown butt ends of rotted trees.

When the water is down, the docks left standing in the muck become long-limbed flamingos, skinny legs and knees exposed. Can-can girls. Frisky ladies pulling up their skirts. The docks that have been hauled out and tied upright to trees show their shiny plastic barrel bellies.

Anything that can blow away has been stored away. Gone are wind chimes and floats, umbrellas and beach chairs. Lonely picnic tables, too heavy to move, dot beaches and yards. They’ve begun their slow, cold wait for weather that will again pull people back outside to sit.

At the marina, docks and boat berths are pulled out. The gas pump is gone. White shrink-wrapped motorboats sit on land like so many Sydney Opera Houses. In the extreme silence, my ears track the progress of a car as it travels from the lakeshore up to the top of a wooded mountain.

On this last paddle, I do things I don’t do when the water is high and others are about. I cross the lake at its widest point, slowly. Today, no need to rush. No worry about powerboats overtaking me before I reach the other shore. I cross and recross. I stop paddling and float with head back and eyes closed, stamping this serene time into my memory.

The loon that lives with his mate in a reedy shallow wants to play. He dives under my kayak and emerges, finally, twenty yards off its other side. The waterfall whose hums and trills are muted in season by the competing sounds of summer activity now has top billing. From my gently rocking seat, I take in its performance.

As I head home, the day’s last rays kissing the earth, I look down the lake and think of what’s ahead. Winter will soon bring its wonders. Like the long skate. If you catch it just right, after the lake freezes but before snow has buried it, you can skate on glass for seven miles.

© Lori Hein splits her time between Boston and the New Hampshire woods and is the author of Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America (www.LoriHein.com). Her freelance work has appeared in publications across North America and online. She publishes a world travel blog at http://RibbonsofHighway.blogspot.com.

September 22, 2006

Fall in Keene, NH: Clarence DeMar and lots of pumpkins

Keene, New Hampshire is a great little city. It’s got college kids and all the fun and funk they bring to a place; the pristine clapboard crispness of elegant, old Victorians; wooded parks and rippling rivers; a double-wide Main Street with a mall down its middle and a gazebo at its end; just the right mix of eclectic, priced-right shops and box stores where you can get stuff like mops and toilet paper. A pretty, peaceful place sprinkled under stone-tipped Mt. Monadnock, reputedly the world’s most-climbed mountain after Japan’s Fuji.

We head into Keene whenever the quiet of the woods surrounding our nearby cottage starts crushing in on us. "To Keene for chicken tacos!"

Fall in Keene brings a few traditions, like the return of Keene State College students, the Clarence DeMar Marathon, and the Keene Pumpkin Festival.

This Sunday, God and hamstring willing, I'm running the DeMar. It’s a tiny marathon – only about 250 runners – and the route is open to traffic, which should be interesting. When my brain is fried at mile 21, I hope divine intervention will pluck me from the path of the oncoming car I’m about to run into. I guess nobody’s been seriously hurt yet, because this race, named for seven-time Boston Marathon winner and sometime Keene resident and teacher Clarence DeMar, has been run since 1978. (For a fun read, try to find a copy of DeMar’s autobiography, Marathon. The dude could run, and his pavement-pounding exploits are fascinating, but his personality quirks are a story unto themselves. The book, out of print, is hard to find, even on Amazon, and what I saw there recently makes me think my two copies are worth much more than the $7.50 each I paid for them at my favorite used bookstore outside Keene: somebody was selling a copy on Amazon for $49.95. )

I drove the DeMar course a few weeks ago and videotaped it so I can practice running it in my head before the real deal. It’s a gorgeous course, which should help ease my suffering.

The race starts in Gilsum, where gems like quartz and tourmaline pepper the ground, and mineral and crystal seekers gather every June for the annual Rock Swap. We take off in front of the General Store, near Mine Street. The course winds through Surry, following the curves of the swift-moving Ashuelot River, and then spends miles wending through parts of Keene I never knew existed. (And up hills I never knew existed.)

After the race I'll repair to Margarita's for red wine and fake Mexican food. Margarita's sits on Main Street and looks onto the site of another Keene fall tradition, the Pumpkin Festival.

It's something to see: over 20,000 jack-o-lanterns lighting the city center in a festival that holds the record for most jack-o-lanterns assembled in one place (over 28,000). The carved pumpkins, lit at night in a spectacular display, sit in tiers on scaffolds, piled in pyramids, and lined up and down every inch of curbing in downtown Keene.

Keene's well worth a trip any time of year, but fall brings its own brand of fun.

www.LoriHein.com

March 21, 2006

Ode to a dirt road

Mud season’s come early.

Most years, the dirt road that leads to our New Hampshire cottage doesn’t turn into a rutted, tire-eating gauntlet of sucking-wet goop until April. But we’ve had a mild winter, and the mountain snows began melting weeks ago. They've begun their trickling meander downhill toward the sea, turning any unpaved ground into sopping, brown sponge. Driving on it tests your focus, your shock absorbers and your windshield wipers; mud splatters and squishes in all directions, including up, covering your car to its roof.

Our dirt road is two and a half miles long. Two and a half gloppy miles into the woods to get to our place and two and a half gloppy miles back out to paved civilization. And, if you get to the cottage and realize you’re out of wine or OJ or toilet paper, well....

I just spent a few days at the cottage. When it was time to head home, I bumped and grinded my way over the muck and pulled into the town dump, my van looking like it’d been dipped in chocolate. “Mud season’s here,” I said to the scraggly man who runs the place. He was in his usual spot, draped over the edge of the dumpster, where he can scan what’s getting tossed and reach in and grab anything he deems useful.

“Yep. Already cost my wife new rotors and a pair of brake pads. Mud got all up inside and clogged everything.”

Over the past 20 years, there’s been intermittent talk about paving our road. And 20 years later, it remains dirt. Why? Because we love it.

A dirt road is a special thing. There’s something essential, challenging, alive about a road whose personae range from wind-whipped dust to hard-baked clay to snow-blown ice to clutching mud. A dirt road is earth, is Earth.

When I run on my dirt road, I see life you don’t see on a paved route. Butterflies resting in puddles, yellow and crimson wings moving like slowly-clapping hands; tiny, translucent salamanders soaking their orange skin in the cool mud; frogs croaking in the grasses that line the road's sloping shoulder; a snowy owl swooping from a tree on one side of the dirt track to a tree on the other; electric-green lichen taking root in the road’s moist, shady dips; worms sleeping in drops left by a recent rain.

In my travels, I’ve journeyed along scores of dirt roads, many in high, wild places like Tibet, Nepal, Peru, Guatemala. In most cases, I was a passenger. I saw and felt the hardscrabble rutted tracks from a seat in a smoke-belching bus; from a jitney crammed with farmers and kids and women with baskets of chickens on their laps; from the rear of a taxi or a hired car or a tour vehicle. To be sure, the experiences were rich, the roads spectacular (and occasionally frightening). But someone else was the driver.

It’s the dirt roads I’ve driven myself that hold the most wonder for me. When my hands feel the roughness of the road through the steering wheel and my feet feel her curves and hollows and stones through the timbre of gas pedal and brake, then the road becomes part of me and I part of it.

It is earth, is Earth.

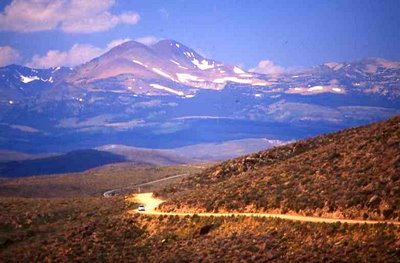

(The photo at the top of this post is Route 120 out of Bridgeport, California, in the eastern Sierra Nevada. The best dirt road I ever rode. While on our Ribbons of Highway journey, the kids and I detoured to Bodie, a perfectly-preserved ghost town. The first 10 miles of Route 120 between Bridgeport and Bodie are paved. Then, as you drive higher into the sky and the purple grandeur of the Sierras wraps itself all the way around you, the pavement ends. The remaining three dirt miles to Bodie are magic.

Read “The ghosts of Bodie,” a story I posted last fall.)

LoriHein.com

June 17, 2005

Homestead and the heart of New England

This is the view from my cottage in Stoddard, New Hampshire, home to 800 souls and an additional 3,500 or so folks like us who spend weekends and vacations on or near seven-mile-long Highland Lake.

We lead a pretty low-tech existence up there. If the rabbit-ear antenna sitting atop our tiny TV is in a good mood, we pick up two television stations -- ABC and PBS. We've become Antiques Roadshow devotees. We have to travel about five miles from our house to get cellphone reception (I pray that no one ever sticks a cell tower on top of nearby Pitcher Mountain), so the kids suffer Nokia and Motorola withdrawl when they're in Stoddard. They compensate by plugging their MP3 players into their ears for the weekend. We have to talk loud to get their attention.

Mike works around the house, relaxes and plays around with his new BlackBerry, a device so addictive we all call it the CrackBerry. I read. I've amassed a huge library by shopping for used bargains at the Homestead Bookshop. I recently wrote an article about the shop for a lovely online magazine called The Heart of New England.

The e-zine, edited by Marcia Duffy, offers glimpses of life in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, but it has readers from all over the world. Duffy has a neat tool -- a Bravenet Guest Map -- on her homepage. I'm a map fanatic, so of course I had to check it out. I found that people from places as far-flung as Wattsville, Alabama, Bainbridge Island, Washington, Australia, France and Turkey get a weekly New England fix from Duffy's magazine. Enjoy some good little New England stories and stick your own pin in the map.

November 29, 2004

Travel treasures in your own backyard

My wake-up call regarding the travel treasures in my own backyard came when I read an article in a major Boston newspaper about -- my town. Damn! I should have written that story! The writer described places and sites a half-mile from my house! But, I couldn't have written that story -- because I'd never visited the places. A freelance writer from somewhere else was smart enough to recognize the destination value of my neighborhood. I was scooped. I missed it. I was too busy looking for travel fulfillment thousands of miles away and had overlooked the treasures down the street.

I now look at nearby places with a traveler's eye, seeking out that which makes them unique or interesting or important, and I write about them, hoping to inspire a traveler with perhaps just an afternoon to spend to go and visit.

I have a cottage on a small New Hampshire lake. In "The Last Paddle," reprinted below, I share a late autumn kayak ride on a lake I've lived on for 20 years, but have only recently taken the time to get to know. "The Last Paddle" was originally published in the November 2004 issue of The Occasional Moose: A Journal of Life in the Monadnock Region:

Foliage is long past peak, many trees already barren. The graying leaves that hang on shake with age and inevitability. I push my kayak into the water and paddle over and around the stumps revealed each October when Highland Lake is peeled back to show things unseen in summer.

Fishermen and weekenders have gone. Time to pull the stopper, inspect the dam and make needed repairs. By Halloween, the lake in its shallowest parts is a ripe mud pool, in its deepest, a glistening meander alongside hushed woods.

It's the season's last paddle. The low water can no longer host powerboats, and even the most committed bass men in their silvery shallow-hulled craft have abandoned Highland until spring. When the lake is down, my kayak shows me things no one else is looking for in places no one else can reach.

I wear sunglasses. Fall's burnished light embraces me and glints off the ripples I ride through. I tilt my face toward the sun, remembering how it felt in summer, trying to soak up and store it.

There's so much to take in, things hidden in high season and high water. A rock jetty, hand-placed long ago, running 15 feet off Mallard Island's tip. The line along the shore where the fecund forest soil ends and New Hampshire's granite underpinnings begin. Decaying logs and slender water grasses, home to creatures, some who show themselves and some who rarely do. I peer into their murky homes and apartment complexes. Hello, turtle. Let me sit and examine the patterns on your shell. The deep, cloying smell of exposed algae fills my head.

Like spotlights, the stillness and bare branches let me see or sense any moving thing. A few year-rounders putter about their properties, canoes on shore, lawn furniture still arranged. Two fishermen are closing their place, pulling up docks and securing windows. Their dog explodes from the woods when he sees me, a burst of movement and color in this muted, going-to-sleep world, and he barks and bounds along the shore next to me until dense trees stop him.

I eavesdrop on a couple in a birch bark canoe. They're a quarter-mile away, but I hear their conversation -- speculation about which yard a moose had called home for awhile -- as clearly as if I were sitting between them. Were I to confirm, in my normal voice, that they'd indeed found Lily Moose's lily bed, they would have heard me, crystal.

Dennis the dentist, who's been spending less time on teeth and more time on the lake of late, poles around on a homemade raft, collecting the slimy, untethered logs that poke from the mud near his dock. A fit, grippingly handsome man with Ralph Lauren hair sharing raft space with dripping brown butt ends of rotted trees.

When the water is down, the docks left standing in the muck become long-legged flamingos, skinny legs and knees exposed. Can-can girls. Frisky ladies pulling up their skirts. The docks that have been pulled out and tied upright show their blue plastic barrel bellies.

Anything that can blow away has been stored away. Gone are wind chimes and floats, umbrellas and beach chairs. Lonely picnic tables, too heavy to move, dot beaches and yards. They've begun their slow, cold wait for people to come back out and sit again.

At the marina, the docks and boat berths have been pulled out. The gas pump is gone. White shrink-wrapped motorboats sit parked like so many Sydney Opera Houses. In the extreme silence, my ears track a car as it moves through miles of woods up on Shedd Hill Road.

On this last paddle, I do things I don't do when the water is high and boats are about. I cross the lake at its widest point, slowly. No worry about powerboats catching me before I reach the other shore. The lake is mine. I cross and recross. I stop paddling, float, and lift my head to the sun, closing my eyes. No need to rush, nothing to watch out for.

The loon that lives with his mate in a reedy shallow across from the marina plays with my kayak, diving on one side and emerging, finally, twenty yards off the other side.

The waterfall whose hums and trills are muted in season by the competing sounds of summer activity now has top billing. I rock in my kayak and note every nuance of its performance.

As I head home, autumn's last rays kissing the earth, I look down the long lake and think of what's ahead. Winter will soon bring its wonders. Like the long skate. If you catch it just right, after the lake freezes but before snow has buried it, you can skate on Highland Lake glass for seven miles.

Read excerpts from Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America at www.LoriHein.com

Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America

"Much more than a travelogue...a captivating story..." MyShelf.com

Order Ribbons of Highway here. Secure and easy. And U.S. readers get FREE SHIPPING

Where Do You Want To Go?

- Andorra (1)

- Argentina (11)

- Austria (5)

- Belgium (1)

- Belize (4)

- Bolivia (10)

- Book excerpts (37)

- Brazil (4)

- Bulgaria (5)

- BVI (1)

- Canada-Alberta (5)

- Canada-British Columbia (3)

- Canada-Nfld (1)

- Canada-NS (3)

- Chile (4)

- China (19)

- Costa Rica (3)

- Czech Republic (6)

- Ecuador (6)

- Egypt (6)

- England (14)

- France (19)

- FWI (2)

- Germany (12)

- Gibraltar (1)

- Grab Bag (84)

- Greece (24)

- Greenland (1)

- Guatemala (3)

- Hong Kong (4)

- Iceland (4)

- India (10)

- Iraq (4)

- Ireland (2)

- Italy (32)

- Jamaica (4)

- Japan (1)

- Jordan (11)

- Jost Van Dyke (1)

- Kenya (17)

- Korea (1)

- Liechtenstein (1)

- Macau (1)

- Malta (9)

- Mexico (3)

- Morocco (2)

- Nassau (1)

- Nepal (8)

- Norway (2)

- Paraguay (1)

- Peru (12)

- Portugal (16)

- Puerto RIco (1)

- Romania (1)

- Russia (7)

- Scotland (8)

- Spain (10)

- St. Barts (2)

- St. John (3)

- St. Thomas (2)

- Switzerland (11)

- Syria (1)

- Taiwan (1)

- Thailand (2)

- Tibet (14)

- Travel tips (14)

- Turkey (7)

- Uganda (13)

- US-AK (1)

- US-AZ (3)

- US-CA (8)

- US-DC (2)

- US-DE (1)

- US-FL (3)

- US-ID (3)

- US-IL (4)

- US-KY (1)

- US-LA (9)

- US-MA (31)

- US-MA. US-NV (1)

- US-MD (3)

- US-ME (1)

- US-MI (3)

- US-MN (1)

- US-MS (2)

- US-MT (1)

- US-NH (13)

- US-NJ (1)

- US-NM (8)

- US-NV (5)

- US-NY (36)

- US-PA (2)

- US-SD (4)

- US-TN (5)

- US-TX (1)

- US-UT (2)

- US-VA (1)

- US-WI (1)

- US-WV (1)

- US-WY (4)

- USVI (3)

- Vatican City (2)

- Virgin Gorda (1)

- Wales (3)

Good sites

- Book Hotels Online

- BootsnAll travel community

- AirFareWatchdog

- Johnny Jet

- Go Nomad

- World Hum

- Journeywoman

- Perceptive Travel

- Vagablogging

- Andy the Hobo Traveler

- Gadling: Engaged Travel

- The Traveler Newsletter

- Budget Travel

- UNESCO World Heritage Sites

- Tourism Offices Worldwide

- TripAdvisor.com

- TravelZoo: Daily deals

- Interhome: Worldwide rentals

- Vacation Rentals By Owner

- European apartment rentals

- KOA Kampgrounds

- America's Byways

- JiWire: All things wireless

- Hotspot Locations

- Cybercafes worldwide

- Telestial - Phones/phone cards

- SpeedyPin Phonecards

- Discounted tours, worldwide

- Rick Steves' Europe

- IgoUgo

- Lonely Planet

- Frommer's Travel Guides

- Fodor's Travel Guides

- Rudy Maxa's Savvy Traveler

- Wikitravel

- World 66 Travel Guide

- Museums Around the World

- Run The Planet

- Most Traveled People

- World Newspapers

- World Airlines

- World Weather

- World Time and Time Zones

- Currency Converter

- Babel Fish Translation Tool

- Magellan's -- travel gear

- CDC Travelers' Health