The security guard and the official building information officer both quizzed and vetted me before handing me to Daniel, a janitor at one of Nairobi’s skyscrapers. I’d asked permission to ride the elevator to the roof for a panoramic view of the city. We agreed on a price, “to be paid later,” and Daniel was tapped to be my guide.

Daniel stashed his broom in a corner under a stairwell and smoothed his bright red cleaner’s smock, torn under both armpits. He led me to the elevator, crowded with workers making their way to the offices and cubicles nested inside the tall building. Daniel gently pushed them aside to make room for me.

We rode to the last stop where the elevator door opened to reveal a ticket booth of sorts. I handed 50 shillings to two giggling Muslim girls in gray headscarves half-hidden behind the opaque Plexiglas of the makeshift kiosk. In unison, they nodded an OK to Daniel. He grinned, said, “This way, please,” and bolted up a concrete staircase to the rooftop helipad, round and high and open to the blue-purple African sky.

Daniel became a bird, his cotton smock feathers and his arms wings as he moved around and across the helipad, mouth laughing, eyes dancing, soul savoring this release from pushing his broom. He jumped from one thick neon-yellow landing sight line to the next, arms outstretched, whirling like a top, canvassing the 360 degrees of Nairobi splendor and squalor laid out below and beyond.

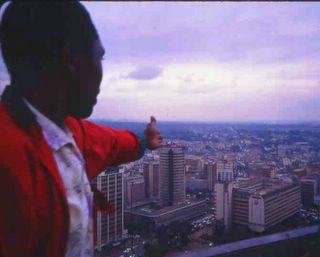

When he came to rest, his arm pointed like the arrow on a board game’s spinner toward Mount Kenya in the northeast. Serendipity or stagecraft? He began my 360-degree tour with this jagged exclamation mark – wild, raw, powerful, like Africa itself. “On a clear day, one can see both Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro from this point,” said Daniel as he tilted his head to the right to find Kili’s snow-capped top.

Over the next hour, one of wonder for me and freedom for him, Daniel moved me counterclockwise around the roof, degree by degree. Each new eyeful triggered talk and tales. The more he could say about the beauty and baseness, majesty and mud, coffee and corruption, the longer he could leave his broom under the stairwell.

Daniel, once a teacher, reveled in the immense embrace of his land. Sharing it gave him great pleasure. He spoke of its problems and possibilities with equal passion.

From the terra cotta roofs of City Hall and the precise walls of the Anglican cathedral, we looked northwest toward the rich, purple Ngong Hills. Daniel talked of the vast tea and coffee plantations there, flanked by wealthy white suburbs. We took in the expanse of Nairobi National Park, whose location hard by the sprawling airport and industrial sector belies its role as a key migratory corridor for big game.

Directly below us a mass of people made its way from Uhuru Park to the office of Kenya’s president and, with a booming collective voice, they asked for an end to the corruption and violence that plague the city and country. Tourists in bathing suits stood at the railing of a luxury hotel’s rooftop pool and watched the scene.

I looked down on the place where the American embassy had once stood. A park now marks the site of al Qaeda’s depraved handiwork. Daniel remembered the day of the terrorist bombing with horror. He sighed deeply and spoke of the “hundreds of Kenyans who will not be there again.” Thousands injured, some left deaf or blind. A passing bus lifted 10 feet in the air, killing all on board. “A noise I never want to hear again,” whispered Daniel, as echoes of the blast seemed to roll through his bones.

Before we came full circle and again faced Mount Kenya, Daniel’s arm swept over the teeming slums of east Nairobi. Land dominion in the north, west and south is held by wealth, wildlife or commerce, so Nairobi’s poor spread eastward. Daniel guided my eyes to the city’s cruelest slum.

“That is where I live,” he said. “With my two young daughters.” He talked about the realities of slum life. His neighborhood has no running water. His daughters are in school, and Daniel struggles to keep them there, learning. Some of his 200 shilling per month salary goes to corrupt teachers and school officials for fake fees and books that never appear. If Daniel doesn’t pay this “money for nothing,” his daughters pay consequences meted out by people a link above him in the food chain. People with just enough power to make a poor family’s difficult life harder.

Clouds began to hug Mount Kenya. Daniel made a last spin around the helipad, his red smock flapping. He tilted his beautiful face upward and smiled at whatever god had granted him this hour’s relief from mop and bucket. I handed him a tip, a janitor's monthly salary, money likely to become money for nothing, and we rode the elevator down to the building lobby.

After a few minutes, I left the building and walked across the plaza, heavy with sober law courts and massive statue of a robed Jomo Kenyatta. I looked back toward the tower. There was Daniel, outside in the sun, smiling softly, sweeping the cobblestones.

www.LoriHein.com