"Entering the Homeland of Jicarilla Apache." The homeland was dry as bone, and Dulce, the reservation’s main town, held no sweetness. Dulce Lake, behind Dulce Dam, was grass and dust. Adopt-a-Highway stretches remembered tribal members like Assegra Luccero, Sea Willow. The Jicarilla Vietnam vets had adopted another piece of this lonely up-and-down road. From here on, for many days and many hundreds of miles, I kept the headlights on. These roads numbed the brain, and I wanted a fair chance of waking the eyes and reflexes of anyone coming at us on these thin strips of sizzling blacktop.

We’d been climbing on Route 64, and when we plateaued, the natural gas industry took over. On high ground, where I got some Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd on Big Dog 96.9, KDAG out of Durango, compressors, tanks, wells, pipes, and holding containers sat unmanned in the desert wilderness. Bright white gas worker pickups populated the road, and when we crested one long rise in the highway at noon, we faced a wall of the white trucks, many from Williams Company, parked at a lone, low building marked "Café," twenty-three miles from Bloomfield, in the middle of nowhere. Lunchtime out in the gas fields.

We came to the green San Juan River, which I will always remember and love. The liquid lifeline hosted a valley and basin that would run green and fertile all the way to Farmington. We first met the San Juan at Blanco, the town a wonderful green relief from the yellow desolation, with fertile fields and trees nurtured by the sweet water. The San Juan and its valley formed a long lush strip that my eyes followed to the horizon for hours, and I missed it when it no longer ran beside us.

We’d entered the Navajo Nation. A sign on the Navajo Missions Communication Center asked people to "Pray For Rain." My fire danger radar had been up in earnest for nearly two hundred miles now, and I sensed things were about to heat up for real. I’d checked the maps for alternate routes, should fire close the roads I’d planned to take, the roads that lived within the lines of the Route Narrative. Parts of the Route Narrative might need to be rewritten. KDAG 96.9, "serving the whole Four Corners area," had thanked firefighters for saving homes and urged them to "stay sane and brave." Not a good sign. Out of the frying pan.

Bloomfield and Farmington oozed into each other, like the natural gas industry that holds them together and keeps them alive. With little else around to please the tourist, Bloomfield’s Dairy Queen, which we would have jumped at anyway, looked like traveler’s heaven behind the heat waves that danced on the blacktop. The vanilla soft-serves made our hours of desert driving feel like a race run once the medal’s around your neck. We got larges this time, and Adam lucked out because Dana couldn’t finish hers.

Shiprock was the reason we were here in this burning hot Bloomfield-Farmington sprawl. My brother-in-law, Jim, once hiked near Shiprock, a dramatic monolith that rises nearly eight thousand feet and dominates the Navajo Nation visually and spiritually. He spoke of its monumental profile, its remoteness, its deep meaning. I value Jim’s opinion on any subject and put Shiprock on my list of things to see if I ever had the chance.

As we drove through the Navajo Nation, we looked on bright blue meat markets selling mutton and lamb to families eating outside on aluminum tables; satellite dishes painted with Indian motifs; a few mud hogans; stores selling two dollar a pack cigarettes; penned sheep; tightly-packed green and gold hay bricks sold from pickups for five dollars apiece; billboards urging teens to practice sexual abstinence; power lines; houses selling "Frye Bread, Sweet Corn, Roast Mutton." And always, there was Shiprock. To the Navajo,

Tse Bit` A`i. Rock With Wings.

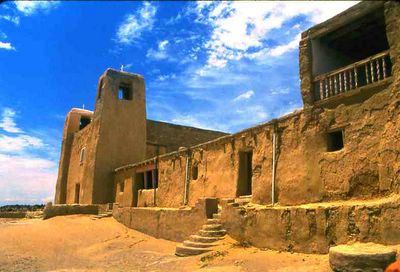

We drove out of Navajo land on Route 666, the Trail of the Ancients. The road was arrow-straight, and when the colossal monolith was no longer in front of or beside us, it sat in the rearview mirror and remained there, gradually filling less and less of it as we neared Colorado. Dana had been reading for a long time. She looked up and out the window. "Shiprock is still there," she said quietly. Like Acoma, a place that always was. A great ship of stone riding the earth, giving the people a link to the past, a grip on the present, and hope for the future.

Click in the right sidebar to buy Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across AmericaLoriHein.com