skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bravo, Lance. Thanks for showing us what it means to live strong. A votre sante.

Bravo, Lance. Thanks for showing us what it means to live strong. A votre sante.

Steve Vaught will pass this mailbox on Route 66 in Tucumcari, New Mexico in the next few weeks, if all goes well.Vaught, a 39-year-old dad and husband from Oceanside, California, is walking across America for a cause. The cause is himself. His own life. Vaught has watched himself change "from a lanky teenager to a muscular Marine" to a fat man, and he's resolved to lose the weight that is robbing him of important pieces of his life. On his website, www.thefatmanwalking.com, Vaught is chronicling the journey that he's undertaken "to lose weight and regain my life."Realizing that there's "no other option but physical exertion," the Fat Man Walking is determined to walk himself thinner and healthier. He set out on April 10, 2005 and will spend six months tracking a route through America that includes much of Route 66, the Mother Road. Vaught anticipates spending six months walking from the Pacific to the Atlantic. To track his progress (he's now in Arizona), wish him well or offer support, visit www.thefatmanwalking.com. Vaught is making a bold move, one labored step at a time. Godspeed, Steve. More power to you.www.LoriHein.com

Steve Vaught will pass this mailbox on Route 66 in Tucumcari, New Mexico in the next few weeks, if all goes well.Vaught, a 39-year-old dad and husband from Oceanside, California, is walking across America for a cause. The cause is himself. His own life. Vaught has watched himself change "from a lanky teenager to a muscular Marine" to a fat man, and he's resolved to lose the weight that is robbing him of important pieces of his life. On his website, www.thefatmanwalking.com, Vaught is chronicling the journey that he's undertaken "to lose weight and regain my life."Realizing that there's "no other option but physical exertion," the Fat Man Walking is determined to walk himself thinner and healthier. He set out on April 10, 2005 and will spend six months tracking a route through America that includes much of Route 66, the Mother Road. Vaught anticipates spending six months walking from the Pacific to the Atlantic. To track his progress (he's now in Arizona), wish him well or offer support, visit www.thefatmanwalking.com. Vaught is making a bold move, one labored step at a time. Godspeed, Steve. More power to you.www.LoriHein.com

Lance Armstrong has a home in Girona, but we didn’t see him. We visited this medieval gem of a city nestled between Barcelona and the Spanish Pyrenees just after Christmas, and Lance and the many other pro cyclists who make Girona their European training headquarters typically move in around February to prep for the race season and leave after October’s final two-wheeled battles.

Lance Armstrong has a home in Girona, but we didn’t see him. We visited this medieval gem of a city nestled between Barcelona and the Spanish Pyrenees just after Christmas, and Lance and the many other pro cyclists who make Girona their European training headquarters typically move in around February to prep for the race season and leave after October’s final two-wheeled battles.

So, with no spectacularly fit guys in Spandex around to distract me, I was able to devote my full concentration to Girona’s haunting medieval beauty and rich layers of history and architecture. Girona is one of my favorite small European cities. Quiet, less-traveled and overflowing with color, character and the simple, honest commerce of everyday life. (The city’s name is spelled Girona in Catalan, Gerona in Spanish. The traveler to fiercely proud Catalonia will find more doors and people open to him if he attempts Catalan first, Spanish second.)

The guidebooks said Girona was an hour by road from Barcelona. Because they show you nothing of a place, I eschew, unless time is of the essence, interstates, motorways, autoroutes, autobahns, autopistas and autostradas equally wherever in the world I find them, picking my way instead along small roads that poke and wind and wend their ways through a land’s real life. The kids and I took seven hours to travel 180 kilometers, meandering along the rugged Costa Brava and detouring up, down and into her villages, ruins and pine forests.

The beauty started at Tossa de Mar, its medieval battlement towering over beach and sea. (The stretch between Barcelona and Tossa was an ugly industrial wasteland.) We listened to CatalRadio, familiarizing our ears with the vaguely Portuguese-sounding Catalan. We bought cans of black olives and mussels (and a salami for Adam) at the supermercat in the resort town of San Felix de Guixols and picnicked on the broad oceanfront promenade. We found Calella, a fishing village bursting with color, where we collected sea glass and inspected tide pools. Pants and coats were called for on that crisp Costa Brava December day, but bundled-up Calellans were out in force. Old men and women sat in groups of three on benches high above the sea, families walked along the sandy beach in front of the wildy-hued line-up of old wooden boathouses, and young boys jumped from one grouping of sea boulders to another, surf crashing onto their pant legs, looking for the next place to cast their rods.

We drove into Girona just as the sun was igniting the ochre, amber, green and blue stucco houses lining the Onyar River into an architectural rainbow. Girona has been inhabited for two thousand years, and the old city (where Lance lives) serves up a dizzying menu of delights, from Roman walls to Arab baths to a mystical medieval Jewish quarter to gothic and baroque churches dating from the 14th to 17th centuries.

Adam sprinted up the massive, vertiginous baroque staircase that leads to Girona’s cathedral. According to the guidebooks -- the ones that declared the trip between Barcelona and Girona to be a one-hour drive -- there are 90 steps. Adam counted 91. My money’s on him. Happy Birthday, Momwww.LoriHein.com

These next two weeks will bring the retirement from major competition of two sports legends, Lance Armstrong and Jack Nicklaus. While Lance eats up the Alps, Pyrenees and hopefully his competition (apologies to my European readers, but you gotta want a guy who is arguably the world’s greatest athlete to go out big), Jack Nicklaus will be driving the formidable hillocks of St. Andrews’ Royal and Ancient into quiet and dignified submission. Waves will crash onto the beach where the Old Course meets the sea, and the 66-year-old Golden Bear will end his stunning career with his final putt in Britain’s 134th Open Championship.

These next two weeks will bring the retirement from major competition of two sports legends, Lance Armstrong and Jack Nicklaus. While Lance eats up the Alps, Pyrenees and hopefully his competition (apologies to my European readers, but you gotta want a guy who is arguably the world’s greatest athlete to go out big), Jack Nicklaus will be driving the formidable hillocks of St. Andrews’ Royal and Ancient into quiet and dignified submission. Waves will crash onto the beach where the Old Course meets the sea, and the 66-year-old Golden Bear will end his stunning career with his final putt in Britain’s 134th Open Championship.

St. Andrews, in Scotland’s Kingdom of Fife, is more than just golf, although it’s pretty heady, even for non-golfers, to soak in the rarefied North Sea-infused air that surrounds the Royal and Ancient’s venerable links and clubhouse. The R&A dates from 1754, and it gave brick, mortar and permanent greens to the sport the Scots invented and have been playing since the 15th century, when sportsmen used sticks to hit pebbles around sand dunes and rabbit runs. Mary Queen of Scots golfed (maybe to unwind and retreat from the intrigues and perils of vying with Elizabeth I for the English throne).

St. Andrews is home to Scotland’s oldest university, and red-robed students stroll Market Street, the broad crescent beach and wooden dock beyond the Old Course, and Kirkhill promenade, a high seafront walkway connecting the ruins of St. Andrews Castle with the ruins of St. Andrews Cathedral (above). (I could hit a golf ball through those holes.)

Back to the Old Course. As rolling and legendary as it is, it has an underbelly. Or a pork belly. As you drive out of St. Andrews, with the history-steeped links of the R&A on your right, there is (or was) a sudden switch from exclusive playground to pig farm. A curious and striking juxtaposition. The links end abruptly at a straight low fence on the other side of which lies the clod-filled black dirt of a potato farm. (It’s been a few years since our visit, and if there’s a strip mall, condo complex or some other horrific blight there now, I don’t want to know about it. In America, farms turn into places to eat, shop or sleep seemingly overnight, and if that potato farm were in the US, the potatoes would be wasting their time putting down roots. I think the Scots are smarter, and I hope the spuds are safe.)

As the kids and I drove past the potato farm, we feasted our eyes on the biggest, fattest hogs we’d ever seen. They poked and snorted their way through the black dirt just beyond the rows of tubers, and some lazed inside mini-Quonset huts built to shelter one huge porcine occupant.

Since pigs eat anything (one reason why I don't eat them), I found myself wondering how many golf balls get plucked from these boys when they get to the sausage factory. Or how many hogs have been hit -- perhaps maimed, causing early dispatch to the sausage factory -- by errant orbs. When Nicklaus recons the Old Course he must make note of all its challenges -- the humps and hillocks, the wind, the trees, the sand, the traps. And the pigs. The Golden Bear will leave it to some duffer to earn the title “Butcher of St. Andrews.”

Every place has a back side. A slice of itself that stays blessedly apart from its tourist side. In Nassau, capital of the Bahamas, located on New Providence Island, the back side is the island’s south coast. The north coast holds all the tourist action, the main town with its Straw Market and British architecture from the days of Victoria and before, the glitzy hotels of Paradise Island, connected to Nassau by a short bridge, and the line-up of big beach resorts.

Every place has a back side. A slice of itself that stays blessedly apart from its tourist side. In Nassau, capital of the Bahamas, located on New Providence Island, the back side is the island’s south coast. The north coast holds all the tourist action, the main town with its Straw Market and British architecture from the days of Victoria and before, the glitzy hotels of Paradise Island, connected to Nassau by a short bridge, and the line-up of big beach resorts.

After a few days hedonizing at a Cable Beach hotel with a few friends, I was getting antsy. I can only do beach for so long before my vagabond soul calls out to see something real, something of the place I’m in and its people. Enough umbrella drinks. I can get those at home. I’m off.

My compatriots were content to lounge on chaises and soak up sun and alcohol, so I rented a moped to circumnavigate New Providence. Had it not been for the trail of fresh appendectomy stitch wounds bothering my mid-section, I would have biked it. A modestly fit rider can take in the whole island in a short day trip. On a moped, you need but a few hours.

I set off on West Bay Street, looking out at the crystal waters that Edward Teach, alias Blackbeard, once roamed. The pirate operated with Britain’s tacit blessing. In the 18th century Britain was waging so many sea battles that the official navy couldn’t handle them all, so seafarers of questionable repute were engaged as privateers, authorized to attack enemy ships for the Crown. The Crown was too far away to rein in the privateers’ loose interpretation of “enemy ship,” which became anything under sail suspected of holding anything of value.

I sputtered westward and rode through hilly stretches peppered with pine forests. I turned south, where, at the coast, the road became Southwest Road. I’d travel the south coast heading east on this road, which changed its name to Adelaide and Carmichael, until I’d turn north again to head back up toward Paradise Island, the city of Nassau, and back to Cable Beach.

It was Sunday. The Bahamas is a deeply religious country. Among its 325,000 citizens, about 18 different faiths are practiced. Sunday is a good day to be out in the island’s small towns and villages.

I came to Adelaide, a tiny village settled by freed slaves in 1832. In that year, a ship of the British Royal Navy intercepted a slave trader bound from Africa for the New World and liberated its human cargo. The freed blacks settled in Adelaide, home today to a few dozen families.

The wooden houses were faded but still riotously colorful, and bougainvillea shaded small lanes and yards alive with vegetable plots and chicken pens.

A bit up the road, I watched families make their way to church. Slim mothers in bright dresses held their children’s hands, and their men brought up the rear. On this brilliant Sunday morning, as tourists on the north coast rolled out of bed and greased themselves up for another beach day, Nassau’s south coast families, in their vibrant Sunday best, held hands and celebrated simple gifts. www.lorihein.com

You robbed them of the only power they have: the power to terrorize. They didn't shut you down, not even for a day. They're hiding, and you're back on your streets, going proudly about the business of living, stripping more of their power away with every step you take. Bravo, Britain.

You robbed them of the only power they have: the power to terrorize. They didn't shut you down, not even for a day. They're hiding, and you're back on your streets, going proudly about the business of living, stripping more of their power away with every step you take. Bravo, Britain.

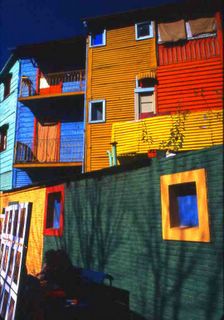

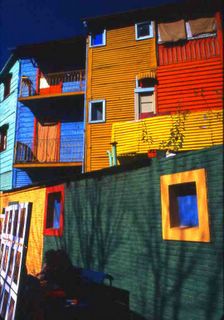

When the conquistadores first came to Argentina in 1516, they found little to conquer or exploit. The native Querandi refused to yield easily, and the arid land held some silver, but not enough to make the Spaniards really dig in. A lasting Spanish settlement was established at Buenos Aires in 1580, but it grew slowly, as the conquistadores and their royal patrons focused more on the riches of Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, loading those lands’ riches into ships, subjugating and breeding with indigenous peoples, and erecting cities filled with ornate colonial architecture. Not until the end of the 19th century, when 50 million people left Europe, did 5 million Europeans immigrate to Argentina and build the cattle industry on which the economy would come to be based. Buenos Aires, meatpacking central and major exporter of beef to Europe, was once called “Nuevo Chicago.” Its colorful Barrio La Boca (above), built hard by the port, was settled by Italian immigrants who worked in the area's warehouses and meatpacking plants.

When the conquistadores first came to Argentina in 1516, they found little to conquer or exploit. The native Querandi refused to yield easily, and the arid land held some silver, but not enough to make the Spaniards really dig in. A lasting Spanish settlement was established at Buenos Aires in 1580, but it grew slowly, as the conquistadores and their royal patrons focused more on the riches of Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, loading those lands’ riches into ships, subjugating and breeding with indigenous peoples, and erecting cities filled with ornate colonial architecture. Not until the end of the 19th century, when 50 million people left Europe, did 5 million Europeans immigrate to Argentina and build the cattle industry on which the economy would come to be based. Buenos Aires, meatpacking central and major exporter of beef to Europe, was once called “Nuevo Chicago.” Its colorful Barrio La Boca (above), built hard by the port, was settled by Italian immigrants who worked in the area's warehouses and meatpacking plants.

Our young Buenos Aires guide, Gaston McKay (“It’s mc-HIGH, like in Scotland”), joked, “In Mexico, they descend from Aztecs. In Peru, they descend from Incas. In Argentina, we descend from ships.” During a long ride out to the pampas, Gaston poked fun at himself and his countrymen, revealing some of their habits and foibles:

“Other Latin Americans think Argentines are Arrogant, Frivolous and Insecure. Arrogant because we are proud of our European descent and are always Europe-looking. Frivolous because of our plastic surgery. Buenos Aires is a plastic surgery leader. And because of our feverish rush around October to get in shape for summer. Come October, everyone runs to the parks, and we might skip a meal – that’s our Ramadan. Insecure because we don’t know who we are. We need cafes so we can talk to others and tell them our problems. We’re all in therapy. There's a section of Buenos Aires that's full of therapists, so we call it 'Village Freud.' We’re the third largest market for Woody Allen films, after the US and France."

Passing Pilar, a gated community on the Pan-American Highway about 40 miles outside the capital, Gaston told us that “it used to be that people lived in the city and had a house in the country. Now, more people are living in the country and commuting into the city for work, especially people with kids. In summer, we are always looking for a pool, so if you have a friend who lives in one of these private communities with a pool, he is your best friend in the summer.”

And Argentines make friends over mate (MAH-tay), an herb that flavors coffee and tea. Everyone has a mate gourd with a metal sipping straw. “We take our mate gourds everywhere,” confirmed Gaston, “at the beach, at the office. Mate means not only tea, but companionship. It means something if you’re going to share your mate. If someone invites you to have a mate, it means they consider you a friend.”

"Argentines used to eat 100 kilos of beef per person per year. A whole cow. We're trying to get healthier, so now we eat only half a cow. We're trying to eat more fish and vegetables, but we miss our beef, our asado, barbecue. We reduce the cholesterol in the beef by drinking wine. Meat with wine is good for you. Meat with no wine is not so good." Siga la vaca!

Notre Dame's rose window gets all the attention, but stained glass junkies looking for an exquisite fix should head around the corner to La Sainte Chapelle, which, like Notre Dame, sits on the Ile de la Cite, ancient center of Paris.Now surrounded by the Palais de Justice, Sainte Chapelle was built from 1246-1248 by Louis IX, France's "Crusader King," to house what Louis believed were pieces of Christ's cross and crown of thorns. The soaring gothic chapel has two levels. The lower chapel was built for the king's servants and contains impressive sculpture and woodwork, but it's the upper chapel that knocks your socks off. Adam climbed the staircase first, and, on entering the royal family's sanctuary, bathed in technicolor sunlight, let out a loud, laudatory "Wow!" The 13th-century windows start at the floor and keep going, and they embrace you on all sides. To stand in Sainte Chapelle on a brilliant afternoon is to indulge in an overwhelming visual feast. Louis IX, who became Saint Louis, went on two crusades, which earned him the epithet "Most Christian King." In a letter to his oldest son, Philip, he offered advice on how to live and rule in a Christian manner. Pieces of his advice, including "...you should permit all your limbs to be hewn off, and suffer every manner of torment, rather than fall knowingly into mortal sin," sound like hilarious soundbites from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Other pieces (see article 32 -- very scary) are downright anti-Semitic, and certainly not very Christian. But his windows are pure poetry.

Notre Dame's rose window gets all the attention, but stained glass junkies looking for an exquisite fix should head around the corner to La Sainte Chapelle, which, like Notre Dame, sits on the Ile de la Cite, ancient center of Paris.Now surrounded by the Palais de Justice, Sainte Chapelle was built from 1246-1248 by Louis IX, France's "Crusader King," to house what Louis believed were pieces of Christ's cross and crown of thorns. The soaring gothic chapel has two levels. The lower chapel was built for the king's servants and contains impressive sculpture and woodwork, but it's the upper chapel that knocks your socks off. Adam climbed the staircase first, and, on entering the royal family's sanctuary, bathed in technicolor sunlight, let out a loud, laudatory "Wow!" The 13th-century windows start at the floor and keep going, and they embrace you on all sides. To stand in Sainte Chapelle on a brilliant afternoon is to indulge in an overwhelming visual feast. Louis IX, who became Saint Louis, went on two crusades, which earned him the epithet "Most Christian King." In a letter to his oldest son, Philip, he offered advice on how to live and rule in a Christian manner. Pieces of his advice, including "...you should permit all your limbs to be hewn off, and suffer every manner of torment, rather than fall knowingly into mortal sin," sound like hilarious soundbites from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Other pieces (see article 32 -- very scary) are downright anti-Semitic, and certainly not very Christian. But his windows are pure poetry.

W

e're heading up to our place in New Hampshire for a long 4th of July weekend. We'll celebrate the holiday in the idyllic village of Hancock, incorporated in 1789. The main street is lined with centuries-old brick and clapboard homes and the Hancock Inn, New Hampshire's oldest inn, which serves a mean Shaker cranberry pot roast. For the 4th, the town puts on an ice cream social in the old church and lights up the sky over Norway Pond with a great fireworks display.I won't be blogging from the New Hampshire woods, so I thought I'd share a short Independence Day-related excerpt from Ribbons of Highway. On America's first 4th of July after September 11, the kids and I had wound our way down deep into Louisiana's Cajun country:On the 4th of July, we found ourselves at Avery Island, home of McIlhenny’s Tabasco Sauce factory. Being a holiday, the factory was closed, and the workers had a day off to crab. We hung at the dock outside McIlhenny’s with 2-year old Trey, his mom Tracy, dad Doug, his grandma, and his “nanonk,” Uncle Travis. (I wondered if nanonk owned Nonk’s Car Repair back up Route 329 in Rynela, near the trailer of the lady that advertised “Professional Ironing.”)

Trey, in his little jeans and bright red rubber Wellingtons, held his hands on both sides of his head and, with eyes wide as plates, told me about what was “in there.” Turkey necks tied to strings and weighed down with washers were the bait of choice of all the crabbers on the dock, and a four-foot gator had decided to come and help himself. He’d just been shooed away and waited on the other side of the canal.

Trey had his own cooler filled with crabs. His parents had a second cooler, so full that when they opened it, crabs spilled out. Tracy and grandma sat on chairs under striped umbrellas and tried to keep Trey from climbing the dock’s fence. Nanonk said, “If’n you fall in, I ain’t goin’ in after ya. Gonna let the gator git ya.”

That night would be America’s first 4th of July night since September 11. All through Louisiana we’d seen evidence that people planned to celebrate with spirit. Fireworks stands were busy. But there’d be caution, too. I’d seen a Times-Picayune story titled “United We Plan” about security measures to protect celebrations large and small around the country. Americans would be out on Independence Day, but with their guard up.

We stood on the balcony of our Bossier City motel and watched fireworks from Shreveport, just across the Red River. Inside the room, James Taylor and Ray Charles entertained on TV from New York City, and two giant crickets tried, unsuccessfully, to elude me.