My daily runs are usually enjoyable experiences, but close encounters of the canine kind can ruin things. I had a dog experience a few days ago, one that sent me to the police station to file a complaint. A husky atop a picnic table on a backyard deck built high above a yard and encircling fence saw me coming, leaped over the fence into the street and held me hostage for ten minutes. This was the third time I’d met this beast on my favorite route, and all the cardio goodness I got from my run evaporated as I blew my top and blood pressure while keeping Mr. Fang from my calves and thighs. (Hey, dog, I need those!) The neighbors who watched but couldn’t help yelled perversely encouraging things like, “So many people have reported this dog!” and “This happens all the time!” and “The owner is a Boston cop, but he doesn’t do anything about it.”

I’ve been pawed, clawed, sniffed, jumped on, growled at, held at bay and bitten by loose dogs whose owners often stand nearby watching the action but taking none. I’ve had my clothes torn, and I’ve been to the ER to confirm the age and protective power of my last tetanus and rabies inoculations. “Don’t worry.” “He’s friendly.” “ He won’t bite.” “He’s more afraid of you than you are of him.” “He’s never hurt anyone.” Oh, had a dime for every time I’ve heard such words.

The dog encounter that most sets my head to shaking was the morning I ran around the dirt roads in the New Hampshire development where we have a cottage and was stopped dead (happily, hyperbole) by two canines, teeth bared, who bolted down their driveway and kept me prisoner in the middle of a considerable hill. I screamed for the owners to come out of the house. They eventually did. (Minutes seem like hours when mouths dripping saliva hang a few inches from your shins and sidequarters.) A mom and two kids ambled, moon-eyed, to the end of the driveway where they stood as a unit and stared at me. They did and said nothing, until the mother finally mumbled, “You’re getting them excited. If you’d just stop running, they wouldn’t come after you…” The three humans stood motionless and watched their animals growl and lunge whenever I made a move to leave. We stood in this stalemate until the dogs got bored and loped back down the driveway.

But this is nothing compared to the dog dread I felt while in Tibet. There, mongrel dogs are everywhere, but they appear in particular abundance at monasteries. (Or, more accurately, ruins of monasteries, as the Chinese, having invaded Tibet [they don't call it an invasion] in the 1950s, successfully obliterated most Buddhist monasteries, epicenters of Tibetan life, during the horrific years of the Cultural Revolution. The Chinese have partially rebuilt some of the temples and monasteries and repeopled them with enough monks to keep them operating as "museums" and tourist attractions.)

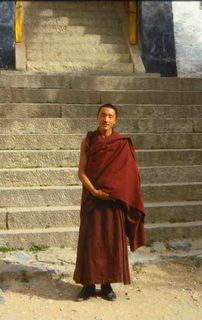

At Sera Monastery outside Lhasa, where monks sit in groups in the treed courtyard polishing their debating skills, a horde of dogs swarmed our vehicle when it pulled into the parking area. As we explored Drepung Monastery , "Rice Heap" in Tibetan, (a Drepung monk in above photo), which hangs on a high hillside outside Lhasa, dogs followed us up and along the warren of dirt paths and alleys that ran through the complex of temples, dormitories and chanting halls.

And there were more dogs in Xegar, a dusty outpost that is a gateway to Mt. Everest. This is a verbatim entry from my journal, written in Xegar’s Everest Hotel (a concrete gulag – I’m low maintenance and extremely easy to please, but this was bad): “Last night I barely slept. Dogs were running wild through this compound all night. There are more dogs in Tibet than you could ever believe. They hang out in massive profusion at monasteries because they get food there. The monks feed them because they believe dogs are reincarnated monks who failed to return to a higher plane. At 4 a.m., I went outside our cell (“suite,” the tour operator called it) to go to the bathroom (a pit latrine), and, as soon as I stepped down the three steps to the dirt yard, two wild dogs tore by my legs. I was scared to death.”

The morning after I wrote that journal entry Mike and I hiked up a mountainside outside Xegar and came to what the Chinese had left of the 800-year-old Shining Crystal Monastery, a walled citadel tucked away on the high reaches of a slope overlooking the beautiful, light aqua river that runs between the last mud-walled houses at the back of the town and distant yellow mustard fields under cultivation. As we climbed, the river pulsed and rippled over mounds of smooth, rounded stone.

We thought Shining Crystal, which once housed 400 monks, was abandoned. It was a shell of what it once was, and we expected to have the striking, firebombed ruin to ourselves. We were at serious altitude, which made us feel even more alone. We were startled, then, when we puffed up the last piece of dirt trail and heard laughter.

Above us, on an ancient, deep red stone arch that framed the mountain trail, sat a half-dozen boys in maroon robes. Little monks. They smiled, swung their feet back and forth in the air and beckoned us to enter. As soon as we crossed the compound’s threshold, dogs appeared. They barked viciously and showed their yellow teeth.

Saved by the monks. The cherub monks shooed the dogs away and then, with great smiles, led us through the passages and warrens and alleys and chambers of the monastery. They showed us everything that was left, everything the Chinese hadn’t disintegrated. We gave the boys pens, hard candy and a few yuan. (They wanted pictures of the Dalai Lama, beloved secular and spiritual leader of all Tibetans, living in exile in India since his escape from Tibet at the time of the Chinese invasion. "No Dalai Lama pics," I said sadly. I’d made a conscious decision not to bring those into Tibet because I didn’t want to be arrested. I applaud passionate activists like the forever-blacklisted-from-China Richard Gere, but I, a weenie, waited until Kathmandu to buy my bright red “FREE TIBET” t-shirt. Just days after we returned home, newspapers ran stories of two Americans who’d been arrested in Lhasa’s Barkhor Square for wearing “FREE TIBET” shirts. Dummies, I thought. You did things backwards. See Tibet first, then buy “FREE TIBET” t-shirt in Nepal. Wear it on the plane home. Make a statement, but stay out of Chinese jail.)

Shining Crystal’s boy monks brought us into the monastery’s main hall, full of images of Tibetan spiritual leaders Dorje Chapa and Songsten Gampo. At the holy chanting hall, where monks young and old were gathered in meditation, Mike was invited to enter, but I, a female, had to remain outside. Mike took his shoes off and went into the deep, close space. I stood at the chanting hall doorway and breathed in the scent of burning yak butter as it escaped in wifts from the sacred, oblong chamber.

Chanting concluded, Mike and the monks emerged from the dark room. Mike put his sneakers back on, and we bowed and touched our fingertips in the universal salaam of friendship and respect, then turned to leave.

On a rock wall above our heads, dogs, growling viciously, shadowed us. We moved, they moved. These beasts would, it was clear, pounce on and eat us before we reached the gate that led back to the world below the Shining Crystal Monastery.

I’d had enough of dogs. Traveling overland across Tibet required considerable endurance, and I was hard pressed to waste any of my remaining energy on dogs. I turned toward the chanting hall threshold in total and complete supplication. An old monk stood in the doorway, and I asked him with my eyes to help us. No words were exchanged, but the spry old guy hopped up onto the wall and, with his arms, kept the canines frozen in place atop the wall until we’d safely exited.

We scrambled down the slope toward Xegar. When we were out of sight, the old monk probably fed the dogs, his yet-to-be-optimally-reincarnated fellows. “I’m sorry,” he might have said. “They’re not all like her. And be patient. Your next lives will be better. Om mani padme hum. Hail to the jewel in the lotus."