I just read the May issue of Smithsonian and had one of those it's-about-time moments. An article by travel writer Tony Perrottet introduces readers to Gerard Baker, appointed in 2004 as Mount Rushmore's first Native American superintendent. Baker, a Mandan-Hidatsa Indian, has, writes Perrottet, "begun to expand programs and lectures at the monument to include the Indian perspective. Until recently, visitors learned about Rushmore as a patriotic symbol, as a work of art or as a geological formation, but nothing about its pre-white history -- or why it raises such bitterness among many Native Americans."

The mountain that holds the monumental heads is, and has always been, sacred ground to the Lakota Sioux and other Indian nations, and it, like the rest of the Black Hills, was stolen by the U.S. government after prospectors under the command of George Armstrong Custer found gold. Perrottet quotes Baker: " 'I'm not going to concentrate on that. But there is a huge need for Anglo-Americans to understand the Black Hills before the arrival of the white men. We need to talk about the first 150 years of America and what that means. ' "

I took my kids to Rushmore on our post-9/11 cross-country road trip, and I did what I could to have them understand what had happened in the high, forested landscape they stood in. In Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America, I wrote:

We were up and out in the morning (after a two-dollar, all-you-can-eat pancake breakfast in the KOA’s Big White Tent) before most of the other 499 sites’ inhabitants, and we had Rushmore’s giant presidential heads and adjacent giant parking lot almost to ourselves.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee had, many years ago, changed my view of pieces of our history, history I’d learned in school in the days before honesty became part of the policy.

In my mind, Mount Rushmore was appallingly insensitive, a monument to manifest destiny cut into the sacred hills of people on the receiving end of the dark side of continental expansion, an inescapably huge reminder of white men’s domination and theft of the Sioux land it towered above. I respected Gutzon Borglum’s artistic accomplishment. And, I respected the presidents portrayed.

It was the act of chiseling them permanently in that particular landscape that bristled me. As we drove toward Rushmore, I asked the kids to consider the land around us and try to understand that these hills, this high, curving earth, these stone pinnacles pointing like fingers into the sky, this forest, these deer by the side of the road, were and are revered by the tribes that had called this place home before white men found gold and killed them or pushed them out. Before the Black Hills became theme parks and fake gold mines and go-kart tracks and wild west shootouts staged for tourists, they were Sioux identity and heritage, and still are. I wanted Dana and Adam to enjoy seeing Mount Rushmore, but I didn’t want them looking at it in a naïve and uninformed vacuum. The rampant kitsch of the Black Hills is dangerous, and I didn’t want my kids to be so seduced or anesthetized by it that they gave no thought to the people whose homeland this had been or, indeed, to the beauty and essence of the land itself...

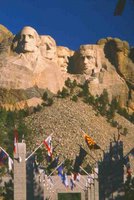

We stood in the wind at the end of a great walkway lined with flags and plaques of all the states of the union and gazed up at four granite men who’d helped create or preserve or defend America and its ideals at some turbulent or pivotal point in its still-young life. I wondered what they thought as they looked down over us now...

By the time crowds and traffic had begun to thicken around Rushmore, portending a sloth-paced touristic sludge by early afternoon, we were far away, first on spectacular Needles Scenic Byway, then on Iron Mountain Road toward Keystone, catching glimpses of the monumental heads across the valley, the stone portraits framed by the orange and pink spires and rock arches and narrow stone tunnels of these thin, twisting ribbons of high forest road.

www.LoriHein.com