Have a spare 17 grand that’s been burning a hole in your pocket? Book a berth on the Shangri-La Express, due to roll from Golmud, China to Lhasa, Tibet beginning in 2007. For $16,995 single occupancy, you can take a deluxe International Railway Traveler Society rail tour of China that begins and ends in Beijing and includes a 20-hour ride on the 713 miles of track the Chinese government is currently constructing to link Golmud with the fabled Tibetan capital. (The UK’s Trans-Siberian Express will operate the train, and National Geographic Traveler magazine reported that tours starting at $5,600 are available through the operator’s booking arm, GW Travel. That may be, but in this blog, I link you only to sites that pass the Lori Hein test, and gwtravel.co.uk, didn’t. Once on the site, a look at their price list requires a download, a step I didn’t appreciate. If you’re interested, you’ve got the URL.)

When completed, the tracks between Golmud, in Qinghai Province north of Tibet, and Lhasa, will be the world’s highest railway line. For most of the journey, passengers will roll along at over 13,000 feet, topping out at 17,146, and pressurized cabins will mitigate the effects of the low-oxygen environment. (Effects like brain-piercing altitude sickness headaches. Mine reduced me to a weeping pile of flesh, and I ate painkillers and sucked on the hose of the oxygen bottle in my Lhasa hotel room to no effect. I waited it out, all the while thinking my head would surely explode and I would die on the floor of the Lhasa Holiday Inn.)

The advent of the Shangri-La Express is remarkable not only for the wonder of its engineering, but because it will make more accessible a place that has, for ages, been among the world’s most difficult to reach. And it’s Tibet’s remoteness that has helped protect and nurture its gentle 1400-year-old Buddhist culture and has given the land its powerful aura of mystery.

This train to Shangri-La is a watershed railroad. A turning point that signals a point of no return for Tibetan culture and no hope of independence from Chinese occupation. In 1958, seven years after they invaded Tibet and a year before the Dalai Lama fled to exile in Dharmsala, India, the Chinese began construction of the Xining-Golmud section of a planned Qinghai-Tibet Railway. That first link opened to traffic in 1984. The Golmud-Lhasa stretch is the final link in the chain. By laying track through Himalayan plateaus and sacred peaks, landscape heretofore considered virtually impenetrable, and establishing a Chinese rail terminus in Tibet’s ancient capital, the Chinese make a statement: Lest anyone still doubt, Tibet is not merely linked to China, it’s chained.

Now for the upside. I’d choose a 20-hour luxury train ride to Lhasa over the two and a half-hour white-knuckle flight Mike and I took from Chengdu to Lhasa any day of the week. Chengdu, in Sichuan Province, is the key air gateway to Tibet. Starting in 2007, Golmud, which is a road gateway, will also be a rail gateway. It’s nice that travelers will have a choice, because our flight was one of the four scariest of my life. (The others? Fodder for another post...)

We took off from Chengdu. The CAAC flight attendants were getting ready to distribute sad little passenger “box lunches” when a voice announced that the plane had “mechanical problems” and we were returning to Chengdu. One of the four engines had shut down. We circled Chengdu, the pilot using the Chinese flying techniques that had been scaring me to near-death on every flight we’d taken in the country. I was sure we’d never see Tibet. We were going down, our quest for Shangri-La doomed to end in a Sichuan vegetable field.

We landed, I kissed the tarmac, then we sat in the Chengdu terminal for two hours. We talked with some businessmen who’d earlier taken off from Chengdu for Chungking (Chongqing), a 40-minute flight. They’d gotten all the way to Chungking but couldn’t land due to fog at Chungking airport. So, the plane flew back to Chengdu, where passengers and crew sat waiting for the fog to lift so they could try again. Fog talk. An ill omen, I thought. I knew the Chengdu to Lhasa flight wouldn’t leave if there were but a hint of fog in Lhasa. Each moment spent repairing our engine gave the elements more time to blow fog toward Tibet. Hurry up! No, never mind! Don’t hurry up! Take your sweet time fixing that engine, and please do it well! I was a bundle of nervous emotion.

We took off again. I was flying to Lhasa, Tibet, the Roof of the World, a place I’d dreamed of seeing since I was a kid devouring copies of my grandmother’s National Geographic. That I was on my way to this fabled place was blowing my mind, but as much as I tried to relax and let the glorious anticipation wrap around me, I couldn’t help fixating on the engine outside my window. Was that the one that had blown? Did they really fix it? Would it die again, causing the insignificant plane to smack into a 20,000-foot ice-encrusted Himalaya? And the pilot. The guy used reverse thrust and other techniques that felt horribly alien. He was going to land us between Himalayas on a short strip of tarmac at the world’s highest airport? Whoa, baby. Never mind the box lunch. Get me a cognac.

About two hours into the flight, on the plane’s left side, a scene of unparalleled beauty revealed itself. We were some 7,000 feet above the highest peaks of the Qionglai-Minshan Mountains (see post below), an eastern range of the Himalaya. My fear and anxiety found new partners, awe and wonder, when I saw what I believe was 24,790-foot Gonga Shan (Minya Konka in Tibetan) – if not her, a near neighbor – pierce the clouds and seemingly rise to meet the plane. Terrifyingly beautiful. Overwhelming, brutal, magnificent.

The sea of glorious peaks we flew over separate the Sichuan Basin from the Tibetan Plateau. A staggering, powerful, vertical white wall that heralds and holds back the magic that is Tibet. Part of this landscape is Kham, (Chamdo in Mandarin), land of strong, quiet horsemen. Part of this landscape was traversed and explored by Joseph Francis Rock, a botanist and adventurer who led the 1927-1930 National Geographic Southwest China-Tibet expedition. His photographs, many of which were published in National Geographic, are a window to the true Shangri-La. That Rock penetrated such a remote piece of the planet to study plants, geography, people and culture still amazes, and in preparing this post I found a wonderful blog by a present-day Rockphile. Click and enjoy.

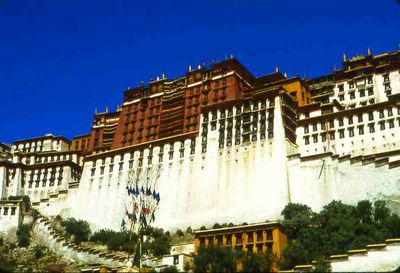

We cleared the high Himalaya. I exhaled. We neared Lhasa. I inhaled. I girded myself for another strange Chinese landing, and the pilot obliged by delivering a horrible gut-girding reverse thrust maneuver, then practically diving for the tarmac. Hey, this isn’t a helicopter, pal. I dug my nails into Mike’s arm and prayed we’d live long enough to see the Potala Palace (above).

Next time, I’ll take the train.