In March, Reuters distributed an article about a London meeting of the world’s biggest polluters. Ministers and leaders gathered to discuss the imperative to reduce carbon emissions. (The US was represented, but, as far as this American can tell, emerged thinking Kyoto Agreement means little more than acting civil while in a lovely Japanese city north of Osaka.)

To spur the ministers to outrage and action, photos were shown of a bald Mt. Kilimanjaro, evident victim of global warming. Kili, 19,340 feet at the tip of Kibo, the tallest of its three summits, sits in Tanzania near the Kenyan border. The highest peak in Africa and one of the world’s highest freestanding mountains, Kili has, for ages, been a symbol of wonder, elusiveness, striving and a source of inspiration and strength. I wrote a story about Tim Saunders, a Massachusetts man who climbed Kili in 2003. “If God lived on earth,” Saunders told me, “I imagine this is what His place would look like.”

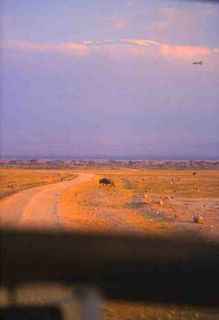

His place looks different now. The snows of Kilimanjaro – Kilima Njaro or “shining mountain” in Swahili – are almost gone. The photo above, taken a few years ago, is the best I could get from Kili. Covered in clouds during most of our visit to Kenya’s Amboseli National Park, the legendary snowcap seemed small and vulnerable whenever it showed itself.

When I read the Reuters article and considered the now nearly snowless Kilimanjaro, my mind flashed back to a van ride across the Bolivian Altiplano.

Adam and I were on our way to Lake Titicaca with Mario, a wizened old driver able to see through roiling clouds of Altiplano dust, and our guide, Federico, a young doctor who had just finished his internship and was trying to qualify for a residency program in Germany. He moonlighted with La Paz’ Crillon Tours to earn extra money for that hoped-for air ticket to Frankfurt.

For two hours, we drove up close and parallel to the Cordillera Real, a string of Andes that blew my mind. From Illimani that looms over La Paz to Illampu near Lake Titicaca, the ride was a nonstop visual feast of some of the world’s grandest peaks.

One looked barren. Chacaltaya was mostly stark brown in comparison to its brilliant, snow-draped neighbors. There might have been more snow on the side I couldn’t see, but Chacaltaya, site of the world’s highest developed ski area, looked rough and rocky. When I suggested to Federico that perhaps the mountain was mad at people for skiing on him, Federico looked at me as if I’d opened a door he never expected me to be able to unlock.

“Every mountain is an abuelo – a grandfather – and a great spirit,” he said softly. “When a mountain loses its snow, it is cause for much concern. We say that the grandfather is taking off his poncho.” When an abuelo takes off his poncho, Bolivians believe the grandfather is preparing to act in some way that will affect the lives of those who live near the mountain. Federico said Chacaltaya had been slowly taking off his poncho for five years.

Kilimanjaro is taking off his poncho. Is he telling us he’s angry at how we treat our world? Kili and Chacaltaya stand on different continents an ocean apart, but the indigenous people who live under both recognize them as elders to be honored, earthforms with spirits. Perhaps the two grandfathers talk to one another, wondering whether mankind will heed the message sent each time another abuelo begins to take off his poncho.

Join me during May at BoomerWomenSpeak.com's Featured Author forum.