(To blog readers: My son is traveling to Greece in April with a group from Massachusetts’ Oliver Ames [OA] High School [see March 5 post]. To give students and parents a glimpse of some of the places on the group’s itinerary and to provide links to sites the travelers may find helpful, I’m devoting 10 consecutive daily posts from March 22 through March 31 to places on the kids’ Greek itinerary. [I can’t think of a better place than Greece to hang, really or virtually, but if you’d like to go elsewhere, cruise the archives to visit scores of other great places, from Jamaica to Jordan, Malta to Mexico.] Wherever you end up, Kalo taxidi! Have a good trip.)

Oh, the intrigue that courses through this ancient place. It infuses every rock, wall, tomb and turn.

Fortress city of warrior-kings, the ruins of ancient Mycenae sit atop a rocky hill ringed by mountains. According to legend, Zeus’ son Perseus built Mycenae with the help of the Cyclops, a race of builder-giants with a single eye in the middle of their foreheads. The city of Cyclopean walls became the seat of the Atreids, a greedy and vengeful family whose sad, sordid story was told by Homer in the Iliad and by tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides (proving that the writer’s nose for a good story goes back to ancient times).

The line-up of accursed, tragic figures who lived, loved, ruled, killed and debauched within and without Mycenae’s walls include Atreus (killed his brother’s sons and served them at a banquet); Menelaus (Atreus’ son and king of Sparta whose gorgeous wife, Helen – the face that launched a thousand ships -- indirectly started the Trojan War); Agamemnon (king of Mycenae who, responsible for leading the fight against King Priam and the Trojans, agreed to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia in exchange for a favorable wind on which to sail to Troy. The goddess Artemis came to the rescue, pulling Iphigenia from the chopping block and sliding a deer in her place.); Orestes (persuaded by his sister, Electra, to kill his mother, Clytemnestra).

Mycenae is not on the list of favorite places to hold a family reunion.

After more than three thousand years, enter Heinrich Schliemann. A retired German businessman obsessed with characters from Homer’s epics, Schliemann began calling himself an archaeologist and persuaded the Turks to let him excavate the presumed site of ancient Troy. He found, and many say irreparably damaged, King Priam’s city, which sits at the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait, across the Aegean from Greece.

Jazzed by what his Trojan excavation yielded – there had, indeed, been a war there in ancient times – Schliemann, who lived and breathed Homer’s Trojan War epic, the Iliad, set out to fit the Mycenaean piece of the Homeric puzzle into its proper historical slots. If Priam and the Trojans had existed on one side of the supposed battle, then Agamemnon and the Mycenaeans must exist on the other.

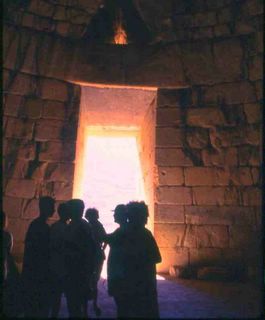

And he found them. In 1876, Schliemann, using lines from ancient texts and stories as clues, started digging inside and to the right of Mycenae’s powerful Lion Gate entrance. He quickly found underground tombs, shaped like beehives (photo above), containing 19 royal corpses festooned with golden face masks, golden breast plates, gold necklaces, bracelets and headdresses. The Atreus clan. Agamemnon and kin.

Schliemann’s discovery was and remains, like Mycenae itself, colored with controversy and intrigue. (Newspapers rode the “Treasure of Atreus” story like seasoned jockeys: from “Amateur archaeologist declares, ‘I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon!’” to stories damning Schliemann’s crude excavation practices, poking holes in his “face of Agamemnon” assertion, and portraying Schliemann and his wife, Sophia, who sat for a photograph wearing pounds of found gold on her head, as thieves and opportunists.) Treasure of Atreus or not, 31 pounds of spectacular gold relics unearthed at Mycenae by Heinrich Schliemann form the centerpiece of the Athens Museum’s Mycenaean Room.

Mycenae is not a joyful place. It broods, in its Cyclopean weightiness, on a gray, weather-beaten hillside.

But everything has its counterpoint. As you wander the ruins, listen for a sparkling tinkle, soft then sonorous, of bells tied to the necks of a thousand sheep being led across the rock-strewn mountaintop by a single shepherd.

Comments or questions? Email me.

www.LoriHein.com