skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I wrote the following post on October 28th and titled it "An egg in Baghdad: The price of UN sanctions." I'm posting it again. The price of the egg, it seems, was driven not only by UN sanctions, but by the UN itself and the rotten eggs that ran and benefited from the oil-for-food program. The original post:

If armed conflict is part of the current fabric of a place, I avoid that place, but conflict sometimes oozes over, around and through borders and colors a journey, nevertheless. In March 1999, I made a surgical strike into Jordan, seizing a period of calm between storms to visit Petra, long at the top of my goals list. I will take you to that exquisite rock city in a separate post.I’d planned to go to Jordan three months earlier, in December, but Saddam Hussein got in the way. He was a bad actor on a good day, and in December, there were no good days.

I wrote the following post on October 28th and titled it "An egg in Baghdad: The price of UN sanctions." I'm posting it again. The price of the egg, it seems, was driven not only by UN sanctions, but by the UN itself and the rotten eggs that ran and benefited from the oil-for-food program. The original post:

If armed conflict is part of the current fabric of a place, I avoid that place, but conflict sometimes oozes over, around and through borders and colors a journey, nevertheless. In March 1999, I made a surgical strike into Jordan, seizing a period of calm between storms to visit Petra, long at the top of my goals list. I will take you to that exquisite rock city in a separate post.I’d planned to go to Jordan three months earlier, in December, but Saddam Hussein got in the way. He was a bad actor on a good day, and in December, there were no good days.

A week before my scheduled departure, the U.S. and Britain began bombing Iraq, and Jordanians joined others in the Arab world in protest. King Hussein, one of the world’s most tireless peacemakers, allowed anti-U.S. demonstrations, provided they were orderly. I kept tabs on State Department travel warnings, loitered in chat rooms at Arabia Online and daily read The Jordan Times Web edition, trying to gauge the mood. Would I be safe? My husband, Mike, and I stayed glued to CNN, watching Christiane Amanpour’s live broadcasts from Baghdad, flak popping behind her, the city’s mosques glowing an eerie neon green. One evening, Amanpour signed off, and CNN cut to Amman, the streets alive with men massed in protest. I looked at Mike. “I’m postponing.” His relief was palpable. I called British Air and rebooked for March.

I landed in Amman one day after the official 40 days of mourning for King Hussein, who’d died from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in February. On the day of his funeral, I’d risen in Boston at 4 am to watch on television, and I cried some. I’d respected this man, a voice of reason and conciliation, for many years. I felt I’d lost a friend and knew the world had lost a man of peace. Ala’a Haddad, owner of the Amman franchise where I picked up my rental car, told me the sight of 40 world leaders gathered to pay final tribute to the king made him proud to be Jordanian. “You cannot know what it was like for us that day,” he said, recalling the feeling of knowing that Hussein, even in death, could make adversaries discover common ground. For a day, Greeks mourned with Turks, Israelis with Syrians, Americans with Iraqis.

As I traveled Jordan and got to know its powerful desert landscape and gracious people, U.S. and British planes dropped bombs daily over Iraq, Jordan’s next-door neighbor, and chased Iraqi planes from the northern and southern no-fly zones. American pilots were busy. Five days after I landed in Jordan, American B-2s began bombing Yugoslavia. NATO had had enough of Slobodan Milosevic. Every night, I’d watch the bombing campaign on television. Every day, I’d sightsee, in my long skirt, long-sleeved tunic, dark socks, flat shoes and headscarf. While America was not alone in pummeling Kosovo and pieces of Serbia, or in bombing Iraq and enforcing economic sanctions, much of the world looked at America and saw arrogance and aggression. I felt a heightened need to blend in. To see Jordan without being seen.

I drove across Jordan to Aqaba on the Red Sea. I stood in the sun on my hotel room balcony and took in four countries with a single sweep of my eyes. The beachfront before me was Jordan. To the left, Saudi Arabia met the sea. On my right, the windows of high-rises in Eilat, Israel caught sunlight and bounced it back into Jordan. Across the Gulf of Aqaba, the mountains of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula sat in a shroud of desert haze.

I turned back into my room and picked up an envelope someone had slipped under my door. In a letter dated March 25, Consul Charles Heffernan of the U.S. Embassy in Amman wrote, “To all U.S. citizens in Jordan: Following the commencement of Nato Military Operations on March 24 against Serbia-Montenegro, there is the possibility for acts of retaliation by Serbians and Serbian sympathizers against Americans and American interests worldwide. The department of state urges U.S. Citizens traveling or residing abroad to review their security practices and remain alert to the changing situation...” A second letter dated March 17 urged traveling Americans to “maintain a low profile, vary routes and times for all required travel, and treat mail from unfamiliar sources with suspicion” because of “Usama bin Laden, the Dar Es Salaam and Nairobi embassy terrorist bombings, the Iraq situation...”

I spent my last night in Jordan at the Alia Gateway Hotel near the airport. The TV in my room offered only a mullah reading from the Koran, so I hung out in the lobby, watching a large, bubbly group of Indonesian hajis enroute to Mecca. The Haj was in full swing, and Amman is a main transit point for flights to Riyadh and Jeddah. While all the men wore white robes, the women’s robes and head coverings spanned the color spectrum. Their pilgrimage brought them such joy that they seemed lit from the inside out.

In the lobby bar, I met an Iraqi expatriate on his way home from Baghdad to Newcastle, England, where he’d lived for 40 years. This was his first trip back to Iraq. He’d gone to see how he could help his relatives, suffering under UN sanctions. Sanctions prohibited direct flights to Iraq, so he’d flown from Newcastle to Amsterdam to Amman, then taken a dusty, 12-hour bus ride to Baghdad. Now, he was making the trip in reverse. He was exhausted, and profoundly sad.“The West has no idea how the Iraqi citizenry is suffering,” he said. He would not call Saddam Hussein by name. “Him. I won’t say the name. He and his cronies are not suffering at all, but the rest of Baghdad is reduced to begging. One of my relatives rents a wing of his house. Now, the monthly rent for that apartment buys one egg.”

The morning moon was still high in the indigo desert sky when I checked in for my flight to London. The London-Amman flight ten days earlier had taken us directly over eastern Europe and the Balkans. The world had changed since then. When all the passengers were seated, the pilot announced over the loudspeaker, “Rest assured that we will be staying well clear of the Yugoslavian conflict...”

Travel can show you the beautiful and the brutal, sometimes in the same journey.

The last time I'd sung all the verses of "Silent Night" in German was in college, when I toted my guitar across campus to my German professor's house. She'd invited her advanced students -- I was masquerading as one -- for hot chocolate and Christmas Stollen, and I hoped a reasonable rendition of "Stille Nacht" might net me an extra point or two on my semester grade.

Fast forward to Christmas Eve, years later, to Wurzburg, Germany's 950-year-old St. Kilian Cathedral. Mike, Adam, Dana and I stood in the great stone church, our breath hanging in the chill air. Yellow candlelight, soft strains of "Stille Nacht," and the fellowship of the hundreds gathered within St. Kilian's soaring Romanesque walls warmed us.

The service ended, and we spilled into the snow-dusted street and fell in with families heading down Domstrasse to the old bridge that crosses the Main. Across the river, the Festung Marienberg crowned a vineyard-studded hill. The nude vines reached upward; thin, dark hands clasped in prayer. The fortress was lit with golden floodlights, and it floated above Wurzburg like a Christmas star.

This Christmas, we pray for peace, our prayers more urgent than in recent past years. We pray for and we thank our troops in Iraq and their families. Whatever our feelings about this war, know that, to a man, we support you. Your courage and conviction, and your sense of duty and loyalty fill us with pride. God bless, and come home soon.

The last time I'd sung all the verses of "Silent Night" in German was in college, when I toted my guitar across campus to my German professor's house. She'd invited her advanced students -- I was masquerading as one -- for hot chocolate and Christmas Stollen, and I hoped a reasonable rendition of "Stille Nacht" might net me an extra point or two on my semester grade.

Fast forward to Christmas Eve, years later, to Wurzburg, Germany's 950-year-old St. Kilian Cathedral. Mike, Adam, Dana and I stood in the great stone church, our breath hanging in the chill air. Yellow candlelight, soft strains of "Stille Nacht," and the fellowship of the hundreds gathered within St. Kilian's soaring Romanesque walls warmed us.

The service ended, and we spilled into the snow-dusted street and fell in with families heading down Domstrasse to the old bridge that crosses the Main. Across the river, the Festung Marienberg crowned a vineyard-studded hill. The nude vines reached upward; thin, dark hands clasped in prayer. The fortress was lit with golden floodlights, and it floated above Wurzburg like a Christmas star.

This Christmas, we pray for peace, our prayers more urgent than in recent past years. We pray for and we thank our troops in Iraq and their families. Whatever our feelings about this war, know that, to a man, we support you. Your courage and conviction, and your sense of duty and loyalty fill us with pride. God bless, and come home soon.

I

got an email recently from Beth, who was getting ready for a Caribbean cruise. Embarking in New Orleans, she'd sail south and visit Cancun, Cozumel, Belize and Roatan, Honduras. A perfect blend of sun-soaked partying and cultural exploration. In Cancun, the cruisers would be offered an excursion to Tulum, an archaeological jewel of the Yucatan peninsula. If you're in Cancun, hop a bus, rent a car, hire a driver, and make the 130-kilometer trip to this Mayan ruin that sits on a bluff high above the sea.

The tentacles of development now reach far beyond Cancun's beaches and boundaries, but the Yucatan's Mayan ruins still offer an enriching experience somewhat removed from the touristic madness. (Go early. You'll have the sites to yourself while everyone else is sleeping off their hangovers.)

We were on the road in our rented VW by seven and were clambering around silent Tulum when it opened. The early start gave us time to visit majestic Chichen Itza the same day. By the time Chichen Itza began to fill with sunburnt tourists, we were headed back to Cancun for happy hour. We stopped at La Posada del Capitan Lafitte, not far from Tulum, and vowed that we'd stay at this low-rise, low-key paradise if we ever returned to the Riviera Maya.

If you visit Cancun, take time to visit the rich history just down the road. Tulum is easily accessible, and you'll congratulate yourself for adding some culture to your Caribbean holiday. Plus, your liver will likely need a rest, anyway. How many umbrella drinks can one person drink in a day? (Never mind. Don't answer that...)

(A special thanks to Beth for purchasing a copy of Ribbons of Highway for the West Bridgewater, Massachusetts public library. I hope townspeople enjoy the journey.)

LoriHein.com

December in Germany is magic. Whether or not you celebrate Christmas, there is no more wonderful place to revel in the wonder of the season. Germans bring the holiday out in the open, with colorful Christmas Markets (Christkindlsmaerkte; Weihnachtsmaerkte) in cities and towns around the country; ancient, cobbled pedestrian areas lined with strings of soft, white lights and decorated evergreens; shop windows bursting with gugels and kugels and kuchen; rosy-cheeked citizens sharing mugs of steaming Gluhwein at outdoor cafes

December in Germany is magic. Whether or not you celebrate Christmas, there is no more wonderful place to revel in the wonder of the season. Germans bring the holiday out in the open, with colorful Christmas Markets (Christkindlsmaerkte; Weihnachtsmaerkte) in cities and towns around the country; ancient, cobbled pedestrian areas lined with strings of soft, white lights and decorated evergreens; shop windows bursting with gugels and kugels and kuchen; rosy-cheeked citizens sharing mugs of steaming Gluhwein at outdoor cafes.

Drive the Romantic Road (Romantische Strasse) from Wurzburg to Fussen, stopping at Rothenburg, Dinkelsbuhl and Nordlingen, where churches and cathedrals tower above city walls that embrace the medieval towns like a good, strong hug.

December days are short here. But when the sun disappears, the magic intensifies. The colored lights glow brighter, and the Gluhwein goes down sweeter. Pack your parka and your mittens, and get out there.

We'd experienced the wonder of the annual Pony Swim from Assateague to Chicoteague Island, Virginia, and Adam, Dana and I were making our way back across Maryland's Lower Eastern Shore toward Washington, D.C. and our flight home. The land between Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic is flat, fertile, and full of history and chicken processing plants.

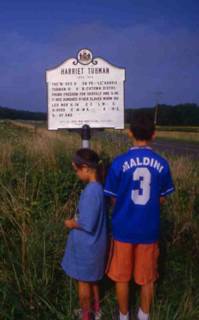

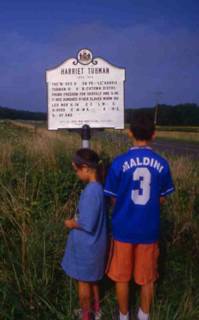

On our way to Chincoteague, we'd seen markers pointing to sites connected with abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman (see post below). "I did a paper on the Underground Railroad when I was in school," I told the kids. "I wasn't much older than you when I wrote it, and I remember how important it felt to learn about slavery and the people who knew it was wrong and tried to stop it." I told them everything I could remember about Douglass, Tubman and the miracle of the Underground Railroad. They listened and looked out the car window.

After five days on Chincoteague, we drove back along Maryland Route 50. It was sweltering, and I thought about the chickens crammed into those endless, hot barracks. Somewhere in Dorchester County, we passed a small sign with an arrow pointing left: "Harriet Tubman Birthplace." No distance; just what you'd find if you covered enough of it to get there.

"Let's go," said Adam. Waiting for us in Washington was an air-conditioned two-room hotel suite and a rooftop swimming pool with a city view. We'd been talking about that pool since we left Chincoteague. "I don't know how far it is, Adam. The sign doesn't say. It may take a while to get there and then back to this highway."

"I want to see it," he said. Dana was game, so we turned left onto a small road and started looking for signs of Harriet Tubman. After a few miles, we'd seen nothing but farms and fields. We stopped to walk among the stones at intermittent old graveyards. When the ride began to seem overlong, even to me, I offered to turn around and head for the Washington pool. "No," said Adam. "Keep going."

On we drove. More hot miles. Farther in time and distance from the cool rooftop pool. Then, outside of Bucktown, we saw a silver-gray historical marker, lit white-hot, stuck in the high grass at a bend in the road. It told of Harriet Tubman, "the Moses of her people."

We read the marker, silently, and turned to consider the broken-down wooden farmhouse nestled under trees at the end of a long, dirt path. The old Brodas farm, where Tubman was born into slavery. We were standing in a field that she likely worked, and she somehow made her way from that house to Philadelphia, and freedom. Only to turn around and come back, a score of times, to lead 300 other human beings to freedom.

There was no one around. Just us and Harriet Tubman. We felt her, and we felt her courage. "I'm glad you wanted to keep going, Adam." He looked at the dark, unpainted house. "Me too."

In the evening, as I watched the kids splash in the pool with a view, I felt proud -- and enriched. Travel brings fun and enjoyment, but it also offers more meaningful gifts. It favors those with open minds and hearts and rewards patience and curiosity. A detour down a Maryland back road had taught my kids something about tolerance, humanity, respect, courage, and right and wrong. That's a lot to gain from one short journey.

(In preparing this post, I came across a website that shares what 2nd graders at Pocantico Hills School in Sleepy Hollow, New York have learned about the Underground Railroad. Click here to read their words.)

We'd experienced the wonder of the annual Pony Swim from Assateague to Chicoteague Island, Virginia, and Adam, Dana and I were making our way back across Maryland's Lower Eastern Shore toward Washington, D.C. and our flight home. The land between Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic is flat, fertile, and full of history and chicken processing plants.

On our way to Chincoteague, we'd seen markers pointing to sites connected with abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman (see post below). "I did a paper on the Underground Railroad when I was in school," I told the kids. "I wasn't much older than you when I wrote it, and I remember how important it felt to learn about slavery and the people who knew it was wrong and tried to stop it." I told them everything I could remember about Douglass, Tubman and the miracle of the Underground Railroad. They listened and looked out the car window.

After five days on Chincoteague, we drove back along Maryland Route 50. It was sweltering, and I thought about the chickens crammed into those endless, hot barracks. Somewhere in Dorchester County, we passed a small sign with an arrow pointing left: "Harriet Tubman Birthplace." No distance; just what you'd find if you covered enough of it to get there.

"Let's go," said Adam. Waiting for us in Washington was an air-conditioned two-room hotel suite and a rooftop swimming pool with a city view. We'd been talking about that pool since we left Chincoteague. "I don't know how far it is, Adam. The sign doesn't say. It may take a while to get there and then back to this highway."

"I want to see it," he said. Dana was game, so we turned left onto a small road and started looking for signs of Harriet Tubman. After a few miles, we'd seen nothing but farms and fields. We stopped to walk among the stones at intermittent old graveyards. When the ride began to seem overlong, even to me, I offered to turn around and head for the Washington pool. "No," said Adam. "Keep going."

On we drove. More hot miles. Farther in time and distance from the cool rooftop pool. Then, outside of Bucktown, we saw a silver-gray historical marker, lit white-hot, stuck in the high grass at a bend in the road. It told of Harriet Tubman, "the Moses of her people."

We read the marker, silently, and turned to consider the broken-down wooden farmhouse nestled under trees at the end of a long, dirt path. The old Brodas farm, where Tubman was born into slavery. We were standing in a field that she likely worked, and she somehow made her way from that house to Philadelphia, and freedom. Only to turn around and come back, a score of times, to lead 300 other human beings to freedom.

There was no one around. Just us and Harriet Tubman. We felt her, and we felt her courage. "I'm glad you wanted to keep going, Adam." He looked at the dark, unpainted house. "Me too."

In the evening, as I watched the kids splash in the pool with a view, I felt proud -- and enriched. Travel brings fun and enjoyment, but it also offers more meaningful gifts. It favors those with open minds and hearts and rewards patience and curiosity. A detour down a Maryland back road had taught my kids something about tolerance, humanity, respect, courage, and right and wrong. That's a lot to gain from one short journey.

(In preparing this post, I came across a website that shares what 2nd graders at Pocantico Hills School in Sleepy Hollow, New York have learned about the Underground Railroad. Click here to read their words.)

Visit other American places in Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America

Harriet Tubman (see above post) is one of the many courageous people, black and white, whose selfless efforts in leading slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad are celebrated in Cincinnati, Ohio's recently dedicated National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Tubman, a Maryland slave, ran north to freedom in 1849. The Railroad's only female conductor, Tubman would make 19 trips south of the Mason-Dixon line to lead some 300 fellow slaves to freedom.

Harriet Tubman (see above post) is one of the many courageous people, black and white, whose selfless efforts in leading slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad are celebrated in Cincinnati, Ohio's recently dedicated National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Tubman, a Maryland slave, ran north to freedom in 1849. The Railroad's only female conductor, Tubman would make 19 trips south of the Mason-Dixon line to lead some 300 fellow slaves to freedom.

L

ast week, a crowd gathered on Boston Common for the lighting of the city's Christmas tree. Like 29 trees before it, the 46-foot white spruce was a gift from the people of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The tree is an annual expression of friendship and thanks for help that Boston provided after the 1917 Halifax Explosion, in which a collision between two ships, one loaded with wartime ammunition, took 2,000 lives, injured 9,000, and left 1,500 homeless.

George Bush recently went to Canada to try to patch the friendship damaged by his decision to go to war in Iraq. While politicians maneuver to mend fences, everyday gestures of friendship between Americans and Canadians remain strong. The delivery of this year's Boston tree reminded me of a personal experience with Nova Scotian friendliness.

I was in Truro, at the head of Cobequid Bay, a finger of the Bay of Fundy. I'd come to watch the tidal bore, an amazing crush of water that rushes toward Truro twice daily, filling Cobequid with a fast-moving wall of water that literally piles on top of itself. I was preparing to experience the evening performance, dramatically lit by a fireball sunset.

I pulled up to a farm that sat at the water's edge. As I began to see water from the distant Bay of Fundy move toward Truro, I realized I'd left my camera at the motel. The woman who owned the farm came outside, and I asked her if I had time to retrieve the camera before the water wall reached us. She considered the liquid shimmer advancing from the horizon and said, "Yes. You have time. But hurry."

I tore up the road and barrelled into the motel parking lot. The owner was waiting at the door, holding it open. "Forgot my camera!" She nodded and smiled.

I got back to the farm just as the water reached the channel neck west of Truro. In a minute or two, the advancing sea would be squeezed into a narrow space, and the aquatechnics would begin. The farmwife stood where I had left her, staring at the bay.

"I knew you would make it," she smiled. I considered the wonder I was about to behold, then considered the wonder I had just been part of. I'm convinced that, through the power of welcome and friendship, the farmwife and the motel owner had held back the tidal bore and made it wait for me.

Ladies, this post's for you. An excerpt from Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America, Chapter 9- Mountains: Northeast Wyoming, Montana. In this excerpt, we're about to leave (sigh) Idaho:In the Conant Valley nearer Wyoming, things turned lush and alive. For single ladies, there may be no better place in the US to see beautiful men than Swan Valley, Idaho, on the South Fork of the Snake River. The Snake here is liquid art. Broad and bending, light sage green, it rushes with small white water, and drifts in silvery ripples. Fingers of treed islands and peninsulas cut and divide it, and wader-clad fishermen cast their arcing lines into its flow, lit by a movie set sun.Swan Valley's population is 260, and it seemed to me a good percentage of that number are fit, gorgeous men, many young, many blond, all quite stupendous. Sit a spell in South Fork Outfitters (where fish-shaped bottles hold the bathroom soap, and a poster above the sink reads, "For Those Who Appreciate the Finer Things in Life, Like Hands That Smell of Fish"). Pick yourself out a fetching paid of hipwaders. But, before you cast your line, for fish or man, you'd better know your way around a driftboat and how to tie a damn good fly, because these boys aren't about looking pretty. They're about serious flyfishing. Looky-loos and dilettantes might earn five polite minutes of their time. Copyright Lori Hein, 2004. Excerpted from Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America

"

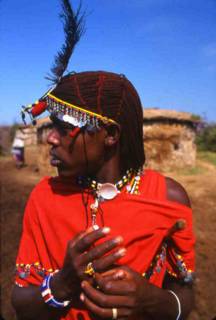

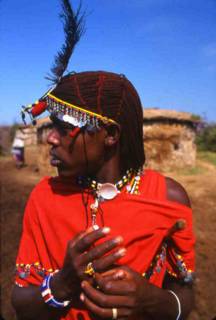

Make as many pictures as you can," said Dixon, turning his head to let me photograph the long braids dyed with red clay that signified his status as part of the Masai (Maasai) morani, or warrior, class. Dixon's 70-member clan earned revenue from tourists visiting their manyatta. The trade was lucrative, and the clan had been living in this location within Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve for three years. They were still pastoralists, their lives centered around raising cattle, but tourist dollars had enticed them into putting down roots and eschewing their traditional nomadic way of life.

Dixon, son of the clan chief, was our host and guide. While he spoke Maa to his clansmen, he talked with us in eloquent, flawless English, perfected during the 11 years he'd spent at a Narok boarding school.

He pointed to the sturdy, dung-walled huts arrayed throughout the manyatta. "Each house is the house of a wife," he said, "and each wife must build her own house." Masai men may have more than one wife and, explained Dixon, they "spend one or maybe two nights within a wife's house and then move on to the house of another wife." Dixon would soon take his first wife, chosen by his father. Dixon would meet her for the first time on the day of their marriage. She was from a different clan and would move to Dixon's manyatta and build herself a dung house. Masai women also maintain their houses and, each morning, they collect cow dung and slap a reinforcing coat onto roofs and walls.

We entered Dixon's mother's house, pitch dark and smelling of animals, dirt, burnt firewood and kerosene. The single kerosene flame that flickered in a corner was useless against the hut's dark closeness, so Dixon opened a tiny vent in the dung wall to allow in enough light to see. We sat on his mother's cowhide-covered bed, a raised mud platform built several feet from the cooking fire. "This is our simple kitchen," said Dixon, as he ran his fingers over and explained all of its contents -- a gourd water calabash, a pot, an iron grate to hold the pot over the fire, and a few sticks of firewood. The Masai diet is exclusively the blood, milk and meat from livestock, "except," explained Dixon, "in times of drought, when the government provides cereals, grains and vegetables."

We heard rustling from a dark recess on the other side of the hut and peered through the blackness to see a pile of children resting in a sleeping nook. The Masai's sleeping arrangements intrigued me, as they involve much moving and arranging of people and animals. When night falls, the cattle come inside the manyatta, the stick fence that surrounds the community affording protection from the Mara's hungry nighttime predators. Lambs and calves sleep inside the huts, in rooms built just for them. Masai men choose their wife du jour (or nuit) and go to her hut. When a man selects a wife and household with children, any boys over the age of 10 must leave the house and sleep in another hut -- one without a visiting husband in it.

So much pre-bedtime shuffling. I'm tired just thinking about it.

LoriHein.com

Where shall we go next?