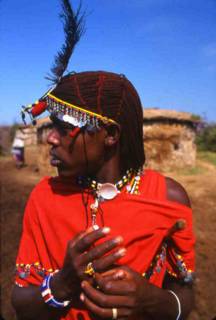

"Make as many pictures as you can," said Dixon, turning his head to let me photograph the long braids dyed with red clay that signified his status as part of the Masai (Maasai) morani, or warrior, class. Dixon's 70-member clan earned revenue from tourists visiting their manyatta. The trade was lucrative, and the clan had been living in this location within Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve for three years. They were still pastoralists, their lives centered around raising cattle, but tourist dollars had enticed them into putting down roots and eschewing their traditional nomadic way of life.

Dixon, son of the clan chief, was our host and guide. While he spoke Maa to his clansmen, he talked with us in eloquent, flawless English, perfected during the 11 years he'd spent at a Narok boarding school.

He pointed to the sturdy, dung-walled huts arrayed throughout the manyatta. "Each house is the house of a wife," he said, "and each wife must build her own house." Masai men may have more than one wife and, explained Dixon, they "spend one or maybe two nights within a wife's house and then move on to the house of another wife." Dixon would soon take his first wife, chosen by his father. Dixon would meet her for the first time on the day of their marriage. She was from a different clan and would move to Dixon's manyatta and build herself a dung house. Masai women also maintain their houses and, each morning, they collect cow dung and slap a reinforcing coat onto roofs and walls.

We entered Dixon's mother's house, pitch dark and smelling of animals, dirt, burnt firewood and kerosene. The single kerosene flame that flickered in a corner was useless against the hut's dark closeness, so Dixon opened a tiny vent in the dung wall to allow in enough light to see. We sat on his mother's cowhide-covered bed, a raised mud platform built several feet from the cooking fire. "This is our simple kitchen," said Dixon, as he ran his fingers over and explained all of its contents -- a gourd water calabash, a pot, an iron grate to hold the pot over the fire, and a few sticks of firewood. The Masai diet is exclusively the blood, milk and meat from livestock, "except," explained Dixon, "in times of drought, when the government provides cereals, grains and vegetables."

We heard rustling from a dark recess on the other side of the hut and peered through the blackness to see a pile of children resting in a sleeping nook. The Masai's sleeping arrangements intrigued me, as they involve much moving and arranging of people and animals. When night falls, the cattle come inside the manyatta, the stick fence that surrounds the community affording protection from the Mara's hungry nighttime predators. Lambs and calves sleep inside the huts, in rooms built just for them. Masai men choose their wife du jour (or nuit) and go to her hut. When a man selects a wife and household with children, any boys over the age of 10 must leave the house and sleep in another hut -- one without a visiting husband in it.

So much pre-bedtime shuffling. I'm tired just thinking about it.

LoriHein.com

Where shall we go next?