Dana's heading to Peru soon for six weeks of intensive Spanish language study. I've been trying to zero in on the best ways for us to stay in touch while she's away and, after many hours of research, here's where I'm at: Facebook gets a like; cellphone gets an unlike. The phone stays home.

I've heard so many horror stories about people getting monstrous cell bills after using (or not using; more on that in a moment) their phones abroad that I wanted to find a foolproof usage method that, if Dana stuck to it, would guarantee that our bills would be merely high, but not heart-attack-inducingly high. I can't find one. With international calls and texts there are many potential layers of cost because multiple steps, carriers and middlemen are involved, and all of them add their charges to your bill.

Even if we disable the data capability on Dana's phone, and make a pact to text rather than call, I realized that just bringing the phone to Peru with international mode enabled invited big bill trouble. Even if you don't read the texts -- or emails, if you stay data-enabled, or listen to the messages in your voice mailbox -- you get charged for them being delivered to your handset. And turning your phone off is not the answer. If international-enabled, the phone still receives and stores emails, texts and voicemails, and you're charged for their transmission.

Dana's a typical 19-year-old with scores of contacts programmed into her phone, and texting is right up there with breathing. I told Dana to tell people not to call or text her while she's in Peru, but that isn't a secure enough plan: she will forget to tell some people; she will tell people by texting them as she's leaving, opening the door for dozens of "hav a gd trip" texts that she'll read in Peru; people who don't know she's gone will call or text her; people will call or text her a week before she comes home to ask when she's coming home; and on and on and on. The possibilities for hundreds of costly messages to make it to Dana's phone during its six weeks in Peru are endless. And the temptation to respond - expensively - is high.

So, no phone. It stays in a drawer in Boston until Dana gets home.

I've come up with a master communication plan that uses the Web and landlines in Peru. Here's how we'll stay in touch:

Dana can access the Web at her host families' homes, her school and at Internet cafes. We'll email, but we'll also do some real time text, audio and video chatting via

iChat (we both have Macs),

Skype and IM. Whenever we're online we'll set our computers to "available" in all those applications. Dana got an

International Student Identity Card (ISIC) to take advantage of discounted airfare to Peru, and one of the bonuses is 60 free minutes of Skype voice credit, so in addition to Skyping online, she can spend up to an hour on talk time to my mobile or landline. In addition to her Mac, she has an iPod Touch, which she can keep in her purse all the time, even when she goes out at night, and if she happens to find herself in a hotspot, can get online to chat or send/read email. All free.

I'm also getting Dana an

AT&T Virtual Prepaid Calling Card. You order online, AT&T sends access codes and dialing instructions immediately via email, and you're good to call. To enable Dana to speak with a US-based, English-speaking operator when she makes a call, I looked up

AT&T's USADirect Peru access codes. From a local line in Peru, she dials that code and gets an operator who then takes her calling card info and puts the call through. She can use the AT&T approach from any landline, even her host families' home phones, and we pay the bill. (Before you buy, read the AT&T website carefully. The prepaid cards' minutes and costs are based on the cost for "state-to-state" calls; international calls ding the card at much higher rates, so delve into the details to understand how many calls/minutes you'll get when the cardholder is calling from a foreign country.)

To enable Dana to use the AT&T prepaid card from a Peruvian payphone, I'll give her money for a local, Peruvian phone card, available at shops and kiosks all over the country. Those cards "turn on" a payphone or a phone at a

Telefonica del Peru outlet, then she punches in her AT&T info, the call goes through, and the card gets dinged.

Finally, we're gonna be Facebook friends. We're not Facebook friends on our existing accounts and don't want to be, but we're going to create second Facebook accounts under variants of our names, and we will be each others' only friend. We can chat freely, for free, and nobody except Facebook will know we're there. We can post and message and "talk," and we'll delete the accounts when Dana gets home. Mark Zuckerberg, I love you.

I shared my masterful, mostly free communication plan with Dana over sushi the other day. She was clearly impressed. "Wow," she said, "you've really been thinking about this."

Yup, AAMOF.

And kiddo, you can always send a postcard.

LoriHein.com

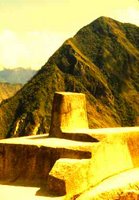

Today, a guest blogger: Dana, who just had an amazing four-day, off-the-grid expedition out of Cusco with about a dozen others from her group. The $100 trip involved some mountain biking on Day One, then hours-long mountain hikes on Days Two and Three. The end of Day Three put Dana's splinter group in Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu, and the terminus for the Cusco to Machu Picchu train. On Day Four the entire group visited Machu Picchu -- but only an early-rising, adventurous subgroup got tickets to climb Huayna Picchu, which is the peak you see in most Machu Picchu photographs. The ruins sit on a flat area between two peaks, Machu, which is never photographed (you stand on it to photograph the famous gumdrop peak), and that gumdrop peak, Huayna, seen here.

Today, a guest blogger: Dana, who just had an amazing four-day, off-the-grid expedition out of Cusco with about a dozen others from her group. The $100 trip involved some mountain biking on Day One, then hours-long mountain hikes on Days Two and Three. The end of Day Three put Dana's splinter group in Aguas Calientes, the town at the base of Machu Picchu, and the terminus for the Cusco to Machu Picchu train. On Day Four the entire group visited Machu Picchu -- but only an early-rising, adventurous subgroup got tickets to climb Huayna Picchu, which is the peak you see in most Machu Picchu photographs. The ruins sit on a flat area between two peaks, Machu, which is never photographed (you stand on it to photograph the famous gumdrop peak), and that gumdrop peak, Huayna, seen here.