Some places are more than places; they're experiences.

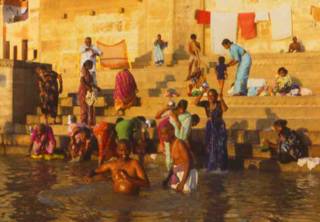

Some places are more than places; they're experiences.Varanasi, India, a city on the Ganges where Hindus come to die so they can be cremated and cast into the holy river, thereby being released from endless reincarnation, is such a place. (Read a 2004 post about our dawn boat ride on Mother Ganga.)

India is sensory overload, and Varanasi is India in 3D and surround sound, a swirl of things competing for space in your brain, the juxtapositions fantastic and overwhelming.

Holy white cows lumbering down the street and horrid black cockroaches scurrying across your hotel floor; corpses burning at one ghat and families bathing in the fetid Ganges two ghats down; sadhus under thatch umbrellas praying with paying pilgrims seeking spiritual enlightenment and refugees from Bangladesh carrying sand in baskets on their heads uphill from the riverbank to a construction site, earning starvation wages of a penny a load.

To escape the intensity, Mike and I decided to go silk shopping. Varanasi silk is world-renowned, and I wanted to bring some home.

We followed the rough directions in our Lonely Planet guidebook and set off up an alley purported to have silk shops. We hadn't been in the street for a minute when a young man in white cotton kurta pajama topped by a vest the color of scarlet betel nut juice sprang before us and said "Hello, and welcome. You wish to buy silk? All hand-made." Like a heat-seeking missile, Ashoka locked onto his targets -- backpacking gringos who turn up the alley broadcast in Lonely Planet -- and went in for the kill. But we did want to buy silk, so we followed Ashoka to his "showroom." I consider that word a euphemism for "place to get ripped off" and prepared for the worst.

The showroom was, like Varanasi, an experience, not a place, and, like Varanasi, I will never forget it.

Ashoka led us up the alley and opened the door to a tiny, hexagonal-shaped storefront on a corner where our alley intersected another. To enter the space we climbed a half-dozen wooden steps set into the street and literally tumbled into a tiny, tower-like room piled high with silk wall hangings. Following Ashoka's lead, we scrambled up the pile and came to rest atop the inventory. We three sat, some 10 feet above street level, cross-legged in a triangle in a round room, ready to do business.

We were sitting on the wares, so, to view a silk, we'd reach behind us or to one side and inspect the ends of it that our body weight wasn't on. If something caught our interest, we'd all shift our weight and Ashoka would miraculously extricate the fabric from the pile and, with a flourish, unfurl it on top. I began to feel guilty about all the work Ashoka was putting in and hoped we'd find something we loved soon, and sort of near the top of the pile. We did.

We both gasped at a five-foot long wall hanging of cobalt blue silk patterned with four exquisite mandalas sewn in gold and copper-colored thread. We paid $50 for the piece, a lot, I thought at the time, but, years later now, I'm sure worth ten times that.

Ashoka wrapped the mandala in tissue paper, we paid him, and we all climbed down out of the hexagonal room onto the street. Mike and I were ready to shake Ashoka's hand and say goodbye when he asked if we'd like to see where our mandala was made.

But it was handmade, no? "Yes," said Ashoka. "I will show you our workshop. It is not far."

We followed Ashoka up the alley to a small, nondescript concrete building with no markings or signage. Ashoka led us around back into a dirt yard and opened a door to a basement. We followed him down the steps into a space so dark I had to give my eyeballs time to adjust.

When they did, I saw rows of women and girls -- there must have been 30 in that small space -- bent over black, cast iron sewing machines, making silk hangings like the one we'd just bought. They didn't look up when we walked in, but kept sewing, in a hot, dank, windowless space lit by naked bulbs attached by bare wires to the ceiling.

Since we bought it, our mandala's hung in whatever living room we've rented or owned. When I look at it I consider its beauty, then wonder which pair of slave hands, working in that dark, dismal underground room, made it.

www.LoriHein.com