Dana just did a geneaology project for her history class wherein she aired our family laundry, some nice, some not. On the not side lies great uncle George Fink, a card-carrying member of the National Socialist party who flew the Nazi flag from his Brooklyn tenement, to the great dismay of his neighbors. He met his death in a New York elevator shaft. There's no official homicide determination, but the word passed through the generations is that George was, shall we say, helped over the brink. "Sorry for your loss," said Dana's teacher.

But we had good folks, too. One of our ancestors was a deckhand on Horatio Nelson's ship during the Battle of Trafalgar. Nelson took a fatal blow, but our ancestor lived to beget a line that would include my grandfather, Steele Pille, who wanted to join the U.S. Navy at 16, but couldn't because he was underage. So he copped an alias and fake papers and overnight became 18-year-old Harry Doubleday (photo below). He spent World War II in France and Japan and rose to Chief Petty Officer. He only revealed his real name to his future bride, my grandmother, shortly before their wedding. "Your name won't actually be Mrs. Doubleday... You'll be a Pille..."

Steele Pille dba Harry Doubleday's father was John Delbridge Pille, a tin miner in Cornwall, England, who emigrated to the U.S. after Cornwall's tin lodes were exhuasted. He moved to Pittsburgh and mined coal. He developed black lung and died in a coal mine accident in Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

John Delbridge Pille (photo above) appears briefly in my book, Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America. I thought of him when the kids and I visited the Empire Mine in Grass Valley, California. An excerpt:

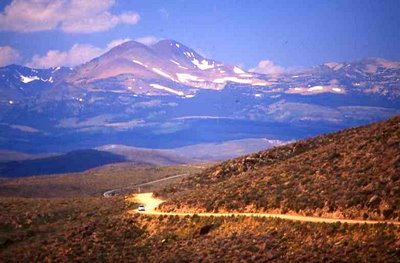

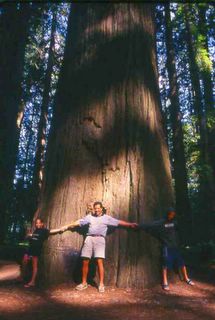

We got off the interstate and took Route 20, a single lane highway that would carry us most of the way across California. The highway changed with the elevation, taking us out of high wilderness down to where the land lost its mountains. It was first a National Forest Scenic Byway, with huge pines hugging the road and vast mountain vistas. Then, it was an artery feeding the huge agribusinesses of the Sacramento Valley. It ended as a winding meander past the string of laid-back lake towns that sit east of the Russian River, the Redwood Empire, and the Mendocino coast.

Latino pickers, wrapped against the sweltering sun in hats, face scarves, pants, long sleeves, and gloves, tended hot fields. Endless alleys of Diamond walnuts, almonds and pecans; strawberries and blackberries; peaches, plums, apricots and nectarines; tomatoes, peppers, cukes and avocados; lemons, melons, grapes and cherries; pears, sweet corn and sunflowers. The Sacramento Valley was wickedly dry, yet still bountiful.

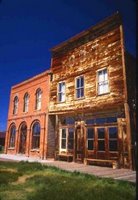

Earlier, we’d detoured into the Gold Rush. The towns of Nevada City and Grass Valley overflowed with magnificent sherbet-hued Victorians, built by Cornish miners to resemble cottages back home. The hilly towns were nonstop eye candy, and I could have walked their streets for days.

At Empire Mine, 350 miles of underground passages and once California’s richest hard rock gold mine, we stood at the top of the slanted shaft and peered down a minute stretch of Empire’s 11,000 feet of total incline depth. Cold air from the bowels of the earth washed over us. Workmen from Gray Electric were in the shaft, building a simulated ride that the foreman explained “will make visitors feel like they’re hurtling down in the carts that brought the miners down.” It was to open at the end of the summer.

“Oh, man!” moaned Adam, lamenting missing this high-speed jolt down into a dark hole in the earth. “We should’ve come here in August!”

I would have liked to go down into Empire, too, not for the hurtling, but to listen to a mine’s ghosts. To hear in the empty tunnels and caves and niches the voices and labored breathing of men, the clink of axes picking slowly and ceaselessly at unforgiving walls of rock, the rattle of pony carts, the drip of water from stone. The grim underearth sounds of men wresting something people deem precious from brutal, sunless holes. Descending into a black mine only lets you begin to grasp the bleakness of a miner’s day and lifetime.

We’d gone down into an old coal mine back in Beckley, West Virginia, where I’d reminded Adam and Dana of their great-great-grandfather, John Delbridge Pille, a Cornish tin miner who’d come to America to mine coal outside Pittsburgh, not all that far as the crow flew from Beckley. Jim, who’d been a miner for 38 years, was our Beckley guide. His grandfather, father, sons, and grandsons had also spent years of their lives underground, working the soft coal of the Sewell seam. We’d traveled in converted coal cars on tracks, down and through the dank pitch of Beckley’s drift mine, nearly horizontal and far closer to the surface than the steep maw of the Empire, at whose entrance, 4,600 miles from Beckley, we now stood.

Jim had pointed out hand-hewn alcoves, some no more than three feet high, telling us to imagine stooping or lying on our backs, swinging a pick for eight hours to loosen the coal overhead. He’d talked of killers unleashed as men cut coal. Methane, released from seams that had held it for ages, exploded. Seeping poison gas displaced fresh air and killed quickly, creating deadly pockets called black damp. Canaries would succumb before humans, so if a miner’s bird died, the man knew he had but a few minutes to escape the area of fouled air.

Now, as I stood before Empire’s steep lip, I wondered if John Delbridge Pille, tin and coal miner, had known any of the Empire gold men. Empire’s success had been built in no small part on the skill and experience of Cornish tin and copper miners who’d left England at the news of California gold. Pille had left England for Pittsburgh about 1840, only a decade before Empire’s first Cornwall miners arrived. Maybe some of the men who’d worked a mile or more down in the cold hole we now stood at had once worked beside my great-grandfather, pulling tin from one of the mines whose stone wheelhouse ruins dot the Cornish landscape like crumbled industrial cathedrals.

www.LoriHein.com