Warning: Reading this post may make your brain explode. (If it doesn't, I guarantee you'll enjoy this post from 2005: "Has Charles Veley Been to the State of Chuuk?")

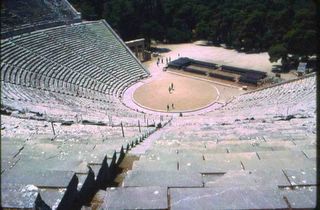

Athens' new Acropolis Museum, scheduled to fully open in September, has a rectangular, glass-walled gallery with a view of the nearby Parthenon. The old Acropolis museum, a narrow, cramped affair that managed, despite itself, to stun visitors with its rich collection of Greek antiquities, may, it's rumored, be turned into a coffee shop. The old museum's holdings, along with breathtaking artifacts from the Acropolis and other Greek sites, have been moved into the new venue.

Key among the new museum's exhibits will be the frieze that once adorned the Parthenon. A room was built to hold it. The rub, of course, is that Greece only owns a few pieces of the frieze.

Most of the pieces -- the marbles -- live in London in the British Museum, which bought them from the British government, which bought them from Thomas Bruce, the 7th earl of Elgin, who took them from the Acropolis in 1801 and shipped them off to England. Lord Elgin, serving as ambassador to Constantinople, had the sultan's permission to slice the frieze into pieces and remove it from then Ottoman-controlled Greece.

Greece would like the Elgin Marbles, which it calls the Parthenon Marbles, back, and the frieze gallery at the new museum is designed to be more than an artistic display; it's a plea for repatriation of priceless pieces of patrimony. The reconstructed frieze will consist of the few original pieces still in Greece's possession interspersed with reproductions of the pieces Elgin took. These lost marbles will be covered in netting, yielding, it's hoped, a powerful visual statement about the cultural crime Greece feels has been committed.

Should the British Museum give the Marbles back?

Loaded question leading to a web of loaded questions. Museums large and small, of all types, all over the world, have stuff that came from somewhere else. So...

If the British Museum gives the Marbles back, should other museums give stuff back, too?

Which museums should give stuff back? Some museums? All museums? Big museums? Small museums?

Which stuff should they give back? Big stuff? Small stuff? Some stuff? All stuff?

To whom should they give it back? To other museums? To countries? What if the countries aren't countries anymore? (Think Mesopotamia and Babylon.)

Should method of acquisition matter in the give-it-back-or-not determination? Museums acquire through purchase or donation, but how did whoever sold or donated get the piece in the first place? And what about absolute provenance -- how an object came to be removed from its true source? Removing outright theft, tomb-raiding, smuggling and other overtly illegal and illicit activity from the equation -- pieces thus acquired should clearly be returned -- what in a piece's bloodline -- from war, conquest and colonialism, to commerce and trade, to excavation and archaeology, both accidental and intentional, whether by amateur hacks or skilled scientists --should or might mark a piece for repatriation?

Should there be an international marble quid pro quo, a supervised global game of marble trading wherein museums -- or countries, universities, foundations, families...-- that get marbles back have to then return marbles they've held, sometimes for centuries, that came from somewhere else?

Imagine trucks and trains and ships and planes loaded with statues and stelae, paintings and pottery, sculpture and sarcophogi, crisscrossing the globe, the transported objects taking each others' places in cases and galleries and on shelves and pedestals. Eventually, if you imagine an endgame in which every item ever removed by any means from its original in situ state finds its way through this great marble trade back to where it was created, every museum in the world would end up being a homogeneous warehouse of stuff from just its own little corner of the world. To see gold and lapis Egyptian death masks, you'd have to go to Egypt. A peek at sublime Tang Dynasty terra cotta figurines would require a ticket to China. To ogle Aztec headdresses, you'd need to book a flight to Mexico. After returning pieces to the places they were born, institutions like the Louvre and the Met could consolidate their remaining holdings into a few rooms and rent out the rest of their space for other uses. Gaze at a Goya then head down the hall for a few strings at the Prado Bowladrome?

Who's got other people's marbles? Nearly everybody. (But not, it seems, the Egyptians or Greeks. Their marbles fit pretty justifiably into some aspect, phase, layer, race or period in their long, complex histories. They've got so many marbles of their own that they've never needed to take anyone else's.)

You can find other people's marbles all over the world.

One day a few years ago, Adam and I followed our guide to the summit of ancient Pergamum  (Pergamom, Pergamon), a glorious citadel-ruin that rises above the modern city of Bergama, Turkey. We came to a large, pedestal-like structure shaded by a few hearty trees that grew in its empty center. "There's not much here now," said our guide of the stripped platform. "The great Altar of Zeus was here, but the Germans took it to Berlin." Indeed, the star attraction and raison d'etre of Berlin's Pergamom Museum is the massive Zeus Altar excavated by engineer Carl Humann during the building of a rail line and sent, in pieces, to Berlin, where it was reassembled.

(Pergamom, Pergamon), a glorious citadel-ruin that rises above the modern city of Bergama, Turkey. We came to a large, pedestal-like structure shaded by a few hearty trees that grew in its empty center. "There's not much here now," said our guide of the stripped platform. "The great Altar of Zeus was here, but the Germans took it to Berlin." Indeed, the star attraction and raison d'etre of Berlin's Pergamom Museum is the massive Zeus Altar excavated by engineer Carl Humann during the building of a rail line and sent, in pieces, to Berlin, where it was reassembled.

If Germany gave the Zeus Altar back to Turkey, would Turkey consider giving some of the goodies it's been holding back to Egypt and other places? Istanbul's Archaeological Museum houses artifacts "discovered" in Cyprus, Palestine, the Arab world and ancient Mesopotamia. It has a collection of sarcophogi found at Sidon, in ancient Syria, and owns mosaic panels from Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar's Ishtar Gate. And, piercing the sky  near the minarets of Istanbul's sublime Blue Mosque is a 16th-century BC Egyptian obelisk from the temple of Luxor that was appropriated and replanted by Byzantine emperor Theodosius in 390 AD. There are only 28 Egyptian obelisks left in the world -- only a few in Egypt. (New York has one, Italy has about a dozen...)

near the minarets of Istanbul's sublime Blue Mosque is a 16th-century BC Egyptian obelisk from the temple of Luxor that was appropriated and replanted by Byzantine emperor Theodosius in 390 AD. There are only 28 Egyptian obelisks left in the world -- only a few in Egypt. (New York has one, Italy has about a dozen...)

If the give-me-back-my-marbles game really took hold, Italy would be mighty busy. It would be on the receiving end of countless Roman, Etruscan and other treasures from museums and venues worldwide. And, it would have some items it might consider shipping back to their places of origin.

Even the Vatican has marbles. (I know, Vatican City is not politically Italy, but if you've ever stood in line in the hot sun to see the Sistine Chapel then, after contemplating the masterwork, sought relief at the gelato shop next door, which sits in Italy, the Vatican is in Rome.) The Vatican's Egyptian Museum holds items won by conquest: the Roman Empire was one heck of a far-reaching enterprise. But if conquest-gotten gains count in the you-should-really-return-this column, the Vatican might have to part with seals from Mesopotamia (we'd better shore up and secure the Baghdad Museum) and bas-reliefs from Assyria, which spans today's Syria, Turkey, Iran and Iraq.

And Venice has marbles. Those four bronze horses over the portal of the Basilica of San Marco?  They once adorned an arch that the Romans built in Constantinople (today's Istanbul). And the Romans allegedly nabbed the equine arch decorations from Greece...

They once adorned an arch that the Romans built in Constantinople (today's Istanbul). And the Romans allegedly nabbed the equine arch decorations from Greece...

Should Greece get its frieze back from England?

I've lost more than a few marbles just thinking about it.

LoriHein.com

They once adorned an arch that the Romans built in Constantinople (today's Istanbul). And the Romans allegedly nabbed the equine arch decorations from Greece...

They once adorned an arch that the Romans built in Constantinople (today's Istanbul). And the Romans allegedly nabbed the equine arch decorations from Greece...