At yoga the other day our instructor, Anne, complimented the class on having attained a level of limberness that let us execute crunches on balance balls without rolling off and crashing onto the studio's wood floor. We students patted ourselves on the backs (a few of us literally, as further demonstration of our increased flexibility).

Over in the corner, Kathy commented that our workouts had also improved her lung capacity. "I went along on a field trip to the

Bunker Hill Monument and climbed all the way to the top without getting winded. I was so excited!" She compared that visit with a previous Bunker Hill foray that had left her gasping for air on the narrow staircase that leads to the monument's observation deck and panoramic view of

Charlestown and Boston's harbor and skyline. "The staircase keeps winding and turning, and people are coming down while you're going up. And there are no windows."

"Like the Statue of Liberty," said Lucia, unfolding herself from a perfect cat stretch. "I climbed up the

Statue of Liberty once and got claustrophobia. Real claustrophobia. I had a panic attack. I was perspiring. I started crying. My son was five, and he didn't know what was happening." A fellow sightseer came to Lucia's aid and guided her to an open air platform where she was able to regroup and steel herself for the trek down.

I felt pangs of sympathy hyperventilation as Lucia recounted her clammy excursion into Lady Liberty's innards. I rolled around on my balance ball and thought about some of the weird, uncomfortable places around the world that I'd stood in lines and paid money to enter. Small, close places I'd have been better off viewing from the outside. High, dizzying places I'd have been better off contemplating from the ground.

The world offers the tourist many places to have a panic attack. Among them:

* Chichen Itza -- I had no problem with the steep climb to the top of the Pyramid of Kukulkan at this remarkable Mayan city in Mexico's Yucatan -- I even sat, smiling, in Chac the Rain God's lap for a rest and photo op when I reached the summit. But when Mike and I ventured inside the chamber behind a staircase at the structure's base for a look at the priceless jaguar statue it held, I freaked out. I imagined the entire pyramid collapsing on my head and pinning me inside the airless, unlit tunnel. A gringo sacrifice to the Mayan gods. I never reached the jaguar -- Mike tells me it was breathtaking -- but before I turned to grope my way back to the exit, I saw two luminescent green balls floating eerily in mid-air at the end of the pitch black passageway: the jaguar's jade eyes.

* Chichen Itza -- I had no problem with the steep climb to the top of the Pyramid of Kukulkan at this remarkable Mayan city in Mexico's Yucatan -- I even sat, smiling, in Chac the Rain God's lap for a rest and photo op when I reached the summit. But when Mike and I ventured inside the chamber behind a staircase at the structure's base for a look at the priceless jaguar statue it held, I freaked out. I imagined the entire pyramid collapsing on my head and pinning me inside the airless, unlit tunnel. A gringo sacrifice to the Mayan gods. I never reached the jaguar -- Mike tells me it was breathtaking -- but before I turned to grope my way back to the exit, I saw two luminescent green balls floating eerily in mid-air at the end of the pitch black passageway: the jaguar's jade eyes.

* St. Paul's Cathedral -- What could be cooler than a climb up into St. Paul's dome, one of the highest in the world? Imagine the sparkling views of merry old London I'd get from up there. I started up the stone staircase, following two 90-pound Japanese girls in stiletto heels, thinking, Piece of cake! London is my oyster! Then the cakewalk turned from broad, stone steps surrounded by reassuringly thick walls to an exposed metal catwalk with near-vomit-inducing gaps between the steps. I couldn't close my eyes, because I'd surely trip and go hurtling over the thin wrought iron armrails and splat unceremoniously onto the stone floor of the nave, a mile below. But I couldn't look, either. A see-through catwalk suspended a hundred feet in the air? Are you kidding me? I need an air sickness bag! I turned around, slowly, and picked my way, squinting, which was a compromise between keeping my eyes open and shutting them tight in terror, to ground level. And way, way up there, the two Japanese girls I'd earlier mentally dismissed as powder-puffy lightweights, pressed onward into the dome, bravely planting their toes and forefeet onto the metal grates and lifting their heels to keep their spikes from getting caught in the gaps.

* Sears Tower -- My architecture cruise on the Chicago River was a highlight of my visit to Chitown. I sat on the boat's top deck with my head tilted back, soaking in the amazing march of magnificent towers that lined both sides of the curving river. When we passed alongside and under the breathtaking endlessness of the black-glass Sears Tower, I couldn't see its top. So, of course, after the boat docked I decided I had to see -- no, stand in -- the top. I walked to the Sears, bought a Skydeck ticket and waited for my group to be called to board the elevator. As we shot up through the shaft at a speed I thought would surely launch us through the roof and into Indiana, the attendant told us about the gargantuan rollers in the 1,353-foot tower's basement that allow it to sway with the prevailing Windy City wind, that literal wiggle room essential to  keeping the Sears from breaking in half and crumbling into Lake Michigan. The elevator opened at the Skydeck, and as I made my way toward the windows that faced Lake Michigan, one or more of those Great Lakes-spawned prevailings pummeled the tower. Which, in response, rolled on its gargantuan ball bearings. I was 1,400 feet above the earth in a moving building. I never even looked out the window. I turned tail and took the next elevator to terra firma.

keeping the Sears from breaking in half and crumbling into Lake Michigan. The elevator opened at the Skydeck, and as I made my way toward the windows that faced Lake Michigan, one or more of those Great Lakes-spawned prevailings pummeled the tower. Which, in response, rolled on its gargantuan ball bearings. I was 1,400 feet above the earth in a moving building. I never even looked out the window. I turned tail and took the next elevator to terra firma.

(In July 2007 construction began on Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava's Chicago Spire, an immensity that will dwarf the Sears. It will be a residential building. I assume it will have its own version of basement ball bearings that will enable the mega-skyscraper to roll with it and blow in the wind. Just the promo video on the Spire's website scares me to death. I can't imagine living in it. Or even going to a dinner party in it. Imagine the host announcing, "No worries, everyone. When the building quiets down and your wine's stopped sloshing up out of the glass, Jeeves will come around with refills.")

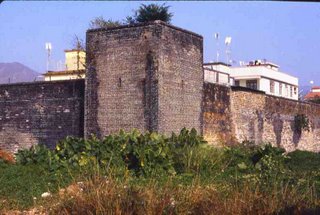

* Ming Tombs -- I should know by now that I do not have the fortitude to handle tourist attractions with the word "tomb" in their names. But when you've spent thousands of dollars and flown three-quarters of the way around the planet to get to a place, you sometimes tune out the voice of experience. In the name of adventure, into the tomb you plunge.

No doubt many Beijing Olympic-goers will take the day trip from the capital -- if only to escape the city's toxic smog for a few hours -- and head to the Ming Tombs, eternal resting place of 15th-century Chinese emperors. I enjoyed the clear air (Whoa! What's that? Blue sky?!) that surrounded the tombs' 40 hilly park-like acres and the 24 larger-than-life-sized animal sculptures

that line the Sacred Way leading to the crypt. When I got to the crypt itself, the fun was over.

that line the Sacred Way leading to the crypt. When I got to the crypt itself, the fun was over.

I followed my guide and a herd of tourists down a ramp into a smotheringly horrific underground space. As I stared at the lineup of royal sarcophogi, the walls started closing in. The ceiling got lower and lower. My eyes rebelled at the strange, thick, gray-dark of the chamber. A fetid stink -- death rot mixed with a noxious-smelling air freshener -- snaked through my nasal passages and attacked my lungs. I told my guide I had to leave. His task was to keep his assigned foreigners in a group and keep his eye on them, so he was disinclined to let me go. "Few minute more. Few minute more." A few minutes more would have rendered me insane, so I apologized to the guide and fled, pushing up the ramp against a new incoming stream of mostly Chinese visitors. To be ebbing when everyone else was flowing defied the cosmic order, but people saw the panic in my eyes and let me pass.

I must not be the only one to have clawed my way, sheet-white and gasping, from the clutches of the Ming Tombs. One online guide to the crypts contains this caveat: "We feel it necessary to remind visitors with heart problems to consider carefully whether they should enter the underground chambers. The atmosphere and dull lighting can be a problem."

I'd add: "If you don't have heart problems when you arrive at the Ming Tombs, there's a better than even chance you'll have some when you leave."

www.LoriHein.com

*

*  keeping the Sears from breaking in half and crumbling into Lake Michigan. The elevator opened at the Skydeck, and as I made my way toward the windows that faced Lake Michigan, one or more of those Great Lakes-spawned prevailings pummeled the tower. Which, in response, rolled on its gargantuan ball bearings. I was 1,400 feet above the earth in a moving building. I never even looked out the window. I turned tail and took the next elevator to terra firma.

keeping the Sears from breaking in half and crumbling into Lake Michigan. The elevator opened at the Skydeck, and as I made my way toward the windows that faced Lake Michigan, one or more of those Great Lakes-spawned prevailings pummeled the tower. Which, in response, rolled on its gargantuan ball bearings. I was 1,400 feet above the earth in a moving building. I never even looked out the window. I turned tail and took the next elevator to terra firma. that line the Sacred Way leading to the crypt. When I got to the crypt itself, the fun was over.

that line the Sacred Way leading to the crypt. When I got to the crypt itself, the fun was over.

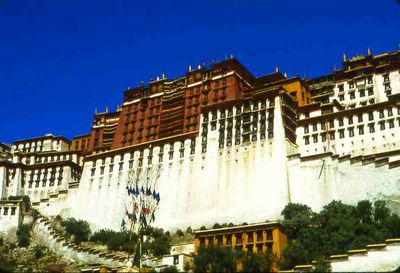

Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy:

Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy: