Hong Kong is one of the most exciting and visually stunning places on the planet. Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, where most visitors spend their time, are nonstop feasts that engage all the senses. A day trip to the less-traveled New Territories offers slices of relative calm and a break from the bright lights of the big city.

Mike and I rode the Kowloon metro north to the end of the line and hopped on a Kowloon Motor Bus headed for Yuen Long, a New Territories district. Our goal was Kam Tin. I’d read about a 500-year-old walled village, Kat Hing Wai, one of the village settlements, or wai, that dot Kam Tin town. We’d been riding Hong Kong’s hyperkinetic wave for days, and I needed a rest, a place where we could ratchet down the pace a few hundred notches. Where better than a remote Ming Dynasty walled village of a few hundred souls?

Bus 64K climbed up into breast-shaped mountains covered in forest and wooded parks. We hopped off the bus before Kam Tin and made a short detour to Lok Ma Chau, a New Territories lookout point that crowns an area sprinkled here and there with rice paddies and duck farms. From the top of Lok Ma Chau, dubbed "Look Ma, China!" during Hong Kong’s run as a British colony, you gaze from Yuen Long district across the Shenzhen River to mainland China and the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, a massive, characterless city where platoons of cheap labor churn out mountains of cheap goods.

After we reached downtown Kam Tin, we walked 15 minutes down a dusty, straight street lined with low, flat-roofed brick houses. Laundry flapped in the blue air and just-made firecrackers dried atop neck-high bamboo racks that ran much of the length of the road.

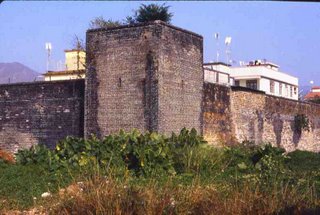

We came to the walled village, which sat in a sea of weeds and scraggly trees, and tall grass grew in what was once the moat. We found the village’s only entrance and stepped into a tight, close world of brick walls and charcoal fires, narrow alleys and dark doorways, greasy windows and small shrines, smoking joss sticks and bicycles at rest. The place is a fascinating, claustrophobic labyrinth of tiny houses, some modern, some dating to the Ch’ing Dynasty.

The first settlement at Kat Hing Wai dates from the late 1400s, the Ch’ing-hua period of the Ming Dynasty. The 18-foot-high walls were added in the early Ch’ing (Qing) Dynasty to protect villagers, members of a family clan called Tang, from roving bands of thieves and pirates. The clan’s Hakka descendants live there today, and Hakka women in bright printed blouses, black slacks and flat shoes pose for pictures for a few yuan. I invested in some shots of Mike bookended by the gap-toothed grandmas in their black lampshade hats.

After an hour in the village’s walled confines, I needed air, and I needed out. When we stepped through the gate into the sun, a Hakka woman seated on a kitchen chair asked us for a small donation. We made a contribution to the preservation of this ancient place and made our way back past the racks of newly minted fireworks to Kam Tin’s bus stop.

Some two hours later Bus 64K deposited us into the bustle of Kowloon. Neon and traffic and skyscrapers and clogged sidewalks and vendors and hawkers and crammed apartment buildings and junks and harbor ferries and clouds of food smells and jars full of snakes sitting in apothecary windows and everybody moving, moving, moving. A wonderful, welcome frenzy.

www.LoriHein.com