I have a book reading tonight at the

West Bridgewater Public Library here in the Boston area. (At 7 p.m., if you're from these parts and looking for a TV alternative.) This "Evening of American Travel" will mix excerpts from

Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America with a slide show of images from across the U.S. Here's an excerpt I'll be sharing:

We crossed the southern Nevada desert on a morning when forecasters down in Vegas promised 110 degrees. I knew we were in for a challenge when we hit Modena, Utah. On the map, it looked like a sizeable border town, and I’d planned to fill up there and take a mental deep breath before we jumped into Nevada.

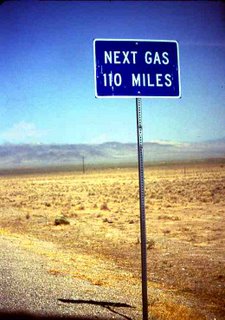

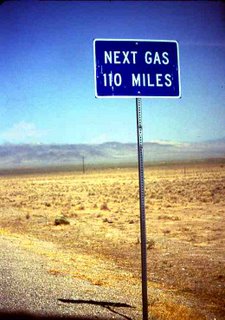

In real life, Modena sat in an elbow-shaped depression off Route 56. We looked down on its tiny entirety from the highway, and I saw nothing inviting. The Nevada crossing was the only point in the trip I’d had any concern about, as the map showed few towns and great, hot distance between them. Looking down on Modena, it hit me that maps are collections of comparisons. Whether something’s written big or small on a map depends on what’s around it that cartographers compare it to. Modena was near nothing, so they wrote it big. That doesn’t mean it has a gas station. If it did, I didn’t see it.

We came to the Nevada line and entered eight hours of utter brown desolation. Leaving Utah felt like stepping off into a giant superheated void. This was the trip’s longest day.

Through all of Nevada, we’d climb about 1,500 feet to the crests of 6,000-foot summits, plateau at that elevation for a while, then drop 1,500 feet to do it all over again. We crested Panaca Summit at 6,719 feet, then coasted about 10 miles downhill into the town of Panaca. We needed gas. We had half a tank and all of Nevada in front of us. Like Modena, Panaca was big on the map. And, it was the last place writ large for a long, long stretch. If Panaca didn’t have gas, we were in trouble.

The town was a shock. Route 319 cut through downtown, where we saw not a soul. There was Panaca Market, a Mormon church, and the Spud Shop, which sold something called spudnuts. No gas station. Was this a joke? Were we in a bad dream? People could buy spudnuts in Panaca, Nevada, writ big on the map, but no gas? My hands clammed up on the steering wheel as I looked clear to the end of Panaca where Route 319 dead-ended at Route 93. I knew we couldn’t leave this town without buying gas, because the map showed a whole lot of hundred-degree nothing beyond it. I made plans. I’d call AAA on the cell phone and have them deliver. I’d flag down passing cars and pay them to siphon gas into New Paint’s tank. I’d find a local rancher and buy up his supply of tractor gas.

Just as I had us putting down temporary roots in Panaca, (“Hi, Mike, it’s us. Just wanted to let you know we’ll be a few days late meeting you in Fort Bragg because we’re living in Panaca, Nevada until we find gas.”) an old service station appeared. It was a full-serve. I laughed out loud, because New Paint needed an oil check, too. Hot dang. Good joss, this!

Two guys were working under the hood of a white pickup. We sat at the pumps for a few minutes, waiting to be full-served. We were three feet from these guys. Neither looked up. There was an old man inside the station. He didn’t come out. I got out of the van and waited. Nothing. I popped the hood and stood there. Not so much as a “be with you in a minute.” Adam got out of the van and stood next to me. We were invisible. “I guess we’ll have to figure out how to check the oil,” I said so they could hear. Nothing. None of the three grown men at this blistering outpost paid any attention to a woman traveling across the desert with two children. Yes, this was a joke, and we were in a bad dream.

I filled the tank and went inside to pay. A trio of slovenly, overweight people was stocking up on 9:30 a.m. chips and soda. The leathery old man behind the counter took my money without looking up. He said nothing. I read all the signs and newspaper clippings he’d tacked up. I figured he wanted me out of there, so I took my time. “Dear IRS, Please Cancel My Subscription.” “If you’re grouchy or ornery there’ll be an extra $10 charge for puttin’ up with you.” “It’s easy to call branding inhumane when you’re sipping wine in Las Vegas.” And the handwritten chart showing mileage between Panaca and other populated places. Beyond nearby Pinoche and Caliente, every other place was triple digits away. I went outside feeling bad. We’d just started Nevada, and it hadn’t shown us anything good.

When I got to the van, one of the guys who’d been working on the pickup had just finished checking the oil and coolant and was teaching Adam how to do it. He told me everything was full, that everything “looked good.” That was all. No other conversation, no questions, no lingering.

But that’s all that was needed to redeem Nevada.

Excerpted from Ribbons of Highway: A Mother-Child Journey Across America. Copyright Lori Hein, 2004

If you go to Las Vegas, peel yourself away from the fabulous Strip and spend at least one evening at the Fremont Street Experience, where Vegas was born. Here you'll find some of Vegas's oldest casinos: the Golden Nugget, Pioneer, Horseshoe, 4 Queens and others.

If you go to Las Vegas, peel yourself away from the fabulous Strip and spend at least one evening at the Fremont Street Experience, where Vegas was born. Here you'll find some of Vegas's oldest casinos: the Golden Nugget, Pioneer, Horseshoe, 4 Queens and others.